The basic three redhead lighting kit used to be a staple of any camera ops arsenal back in the day. So what's the best modern alternative? Phil Rhodes takes a look at what the options are.

There was a time when it was reasonably easy to pick a lighting kit for the most common sort of factual video work. Go to Ianiro or Photon Beard, pick up one of those soft cases containing a kit of three Redheads, and lay a credit card on the counter. Easy.

It was a little inflexible, given the need to clip increasingly-scorched 216 diffusion to the barn doors in a desperate attempt to produce something that didn’t look like mid-80s local TV news. The need to control and modify light has barely changed, and we’ll likely return to the subject of flags, stands, reflectors and diffusers because they’re as relevant now as ever. As to actually generating light, on the basis that we’d rather avoid the 2400-watt power consumption of that redhead kit, let’s ponder the alternatives. Small, portable lights are what LEDs do well.

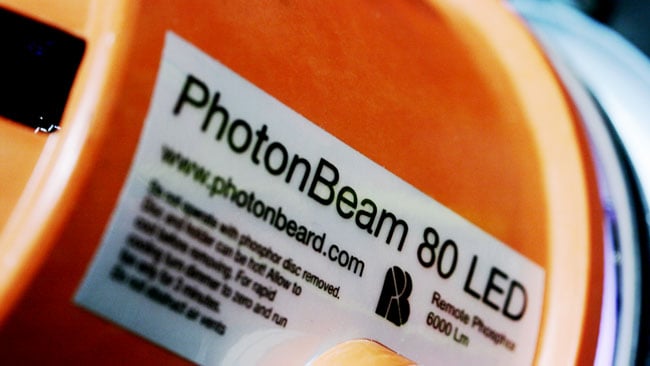

Photon Beard's LED Redhead

The Redhead is dead. Long live the Redhead

Though actually, we can stick to Redheads. Photon Beard’s PhotonBeam 80 is an LED retrofit of the classic design. At 80 watts, it isn’t as powerful as a conventional Redhead, which is generally fitted with an 800W bulb. The efficiency offset between tungsten-halogen and LED is maybe 4.5:1, so the PB80 has around half the output. On the upside, it’s a remote phosphor light with interchangeable panels for tungsten or daylight, and at about £2 a watt, represents a decent value proposition for the power level.

Primitive as open-faced lights are, they have the benefit of huge efficiency; there’s nothing there to stop the light getting out. That’s what we found when examining Photon Beard’s other technological upgrade to a classic, the Platinum Blonde (£3295), which extracts more or less every possible photon from a 1200W HMI and fires it at the subject. It’s probably overkill for a portable kit, and like any open-faced light, it is something of a blunt instrument. Many applications of lights like these – whether they’re tungsten-halogen, HMI or LED – will end up using modifiers that you have to carry around.

Platinum Blonde. 1200W of HMI is a lot, really a lot, in a blonde shell

Still, you might go for an open-faced LED like the PB80 for a hard backlight, perhaps. For soft keying our subject, it’s difficult to beat the efficiency of an LED panel. The choice is both easy and complicated because there are such a huge variety. Arri show an ENG cameraman at work in some of the Skypanel promotional material, which possibly stretches credibility a little, but neither will a thoroughly pocket-sized Aputre AL-M9 fit the bill. For the jobbing cameraperson, portability is key, but there will occasionally be a need to fill in harsh daylight so a reasonable power level is important.

Litepanels will offer a few things with a considerable saving per watt over Arri, but there are even less expensive options. Nanguang has a 200W bicolour panel in its Compac (sic) range covering 3200-5600K; they’re £1200 for a pair. You can even get a full colour panel for less than twice as much, with Rayzr’s MC120 listing at around £850, although some people might conclude that party colours are sufficiently rare that the smarter spend would be on a few more watts of white (read all about it). At the high end of panel lights are manufacturers such as Rosco DMG, Cineo and of course Kino Flo, whose products compete more or less directly with Arri in both price and power level.

Aputure's LS1C typifies devices of its class, although at 120W the power density is high and the scattered emitter layout effectively reduces shadow segmentation

Hard and soft combinations

Combining hard and soft lights in a portable kit, rather than carrying hard light and then softening it to taste, is largely a product of the LED age, give or take a few Kino-Flos that might have been carried by ENG and documentary people. Interchangeable optical front-ends for lights, popularised by manufacturers including Aputure and Hive, is rather newer, at least in moving pictures. The concept comes from the still photography world and the Bowens mount has become a de-facto standard, as on Aputure’s options. Hive’s lights (ranging in power from 25W upward, but perhaps most comparable in their 75W, full-colour-mixing option) have a mount of their own design and are more of a beam-forming PAR arrangement by default, with specular reflectors, while Aputure’s reflectors have also now been improved with a high-gain option.

Hive's light mounts a Source Four Mini lens tube, which is compact

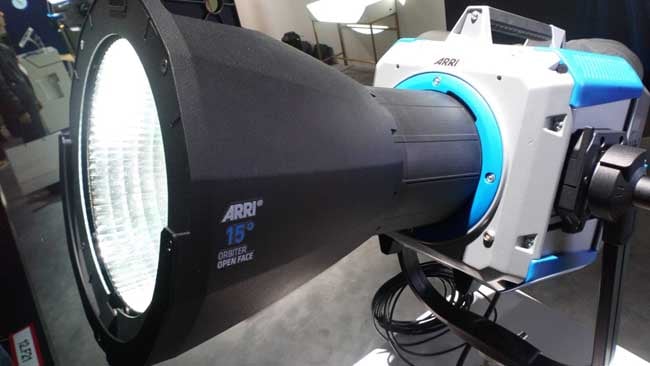

The accessory options are comparable. Hive has a lens barrel adaptor so that their lights can drive a Source Four Mini lens tube. Aputure designed the larger device it calls the Spotlight Mount. A bigger hole lets more light through, although Aputure’s lens tubes are rather like carrying a whole extra light, and are more expensive than Hive’s option. Profiles are a bit of a luxury, perhaps; both companies also have routes to a Fresnel (or at least Fresnel-style) which might find more day-to-day use. And yes, Arri have the interchangeable-lens Orbiter, handling a nominal 400W, though at an estimated $7000 the blue-and-silver option is neither the cheapest nor the most portable.

Arri's Orbiter is flexible, powerful, and rather large and expensive_ not a documentarian's tool

Colorimetry

Perhaps the biggest concern is colorimetry. LED colorimetry is largely a solved problem in the context of a single light, but mixing products, especially across manufacturers, raises the possibility that things may not match precisely, even if they should on paper. For this reason, finely adjustable colour temperature and green-to-magenta shift is important. It’s also rare; only at the top of the market do manufacturers like Fiilex create lights that routinely include these adjustments. The 320W Q8 Travel (listed online at around US$3000) is, despite the “travel” appellation, not a lightweight or inexpensive light, but it’s powerful and controllable.

Fiilex Q8 Travel. We hope one day all LED lighting will be this controllable, but right now, that's an ambition

In fact, price is really the biggest complaint. Options have exploded, but so have costs. Reasonable Redhead kits can be had new for a few hundred pounds. The least-expensive light we’ve mentioned is also a few hundred, for one, no stands. But tungsten is not battery-powerable, gets hot, can’t do daylight, and drifts when dimmed. It’s hard not to consider LEDs to be progress, and in the end, there’s nothing stopping us buying tungsten if we’re skint, keen to reach for the old school, or simply looking for something on which to cook a pie.

Tags: Production

Comments