We continue our series on building a workstation with another highly important component, memory. How do you choose what to buy?

Of all the components of a computer, memory is the one which has changed the least since the early days, at least in terms of its purpose and how it's specified. Even in terms of the way it's supplied and handled, on little plug-in circuit boards, has barely changed in decades.

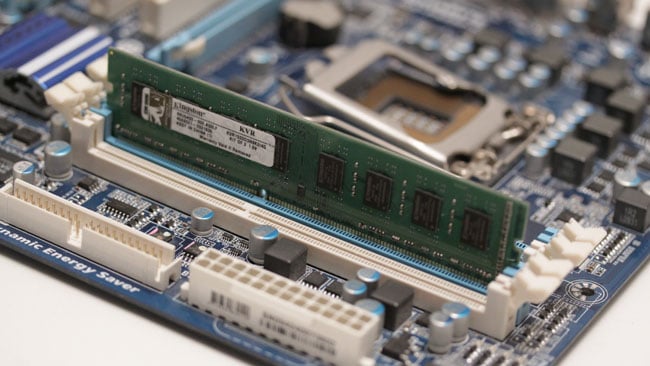

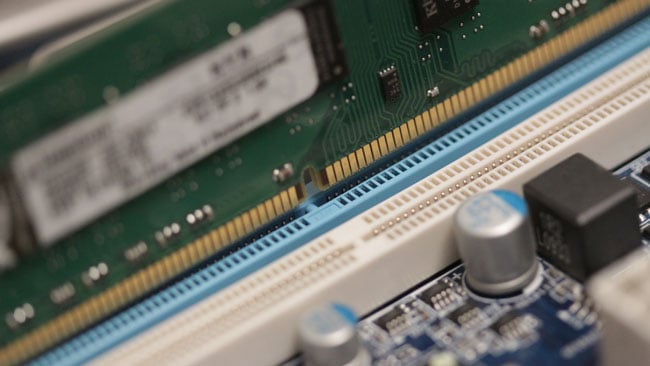

Installing a memory module into a computer motherboard

RAM types

In 2018, most computers capable of serious video work will need at least 16GB of RAM, which will be supplied on dual-inline memory modules (DIMMs.) Memory only comes in a few types, with the most relevant at the time of writing being DDR3 and, more recently, DDR4. The alphabet soup, in this case, arises from the modules operating with a dual data rate, transferring data on both the rising and falling edges of the clock signal, but that's an implementation detail we don't need to worry about much.

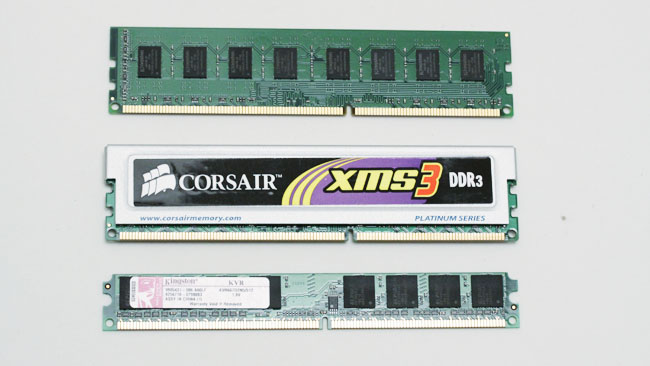

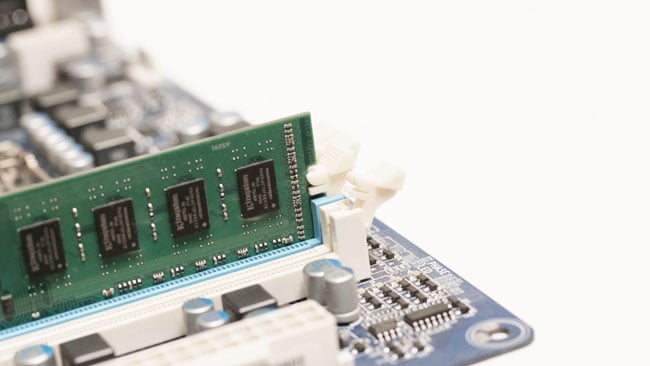

The top two modules are DDR3, the bottom is DDR2. Notice that the notch in the edge is in a different place

Upscale motherboards using AMD Epyc or Intel Xeon processors – those intended for building big servers or particularly powerful workstations – may need ECC memory. This refers to the error correcting code, which improves reliability and can prevent certain types of error-causing problems that may crash a program or even a whole computer. It's more expensive, but it's not a bad idea. Post production work involves a lot of data – really, a lot of data – and the likelihood that a stray cosmic ray will randomly corrupt a single bit of memory becomes high if, for instance, we're rendering a digital cinema package over several days. The pitfall here is that some types of ECC RAM will fit in slots intended for non-ECC RAM, and vice versa, which can cause problems.

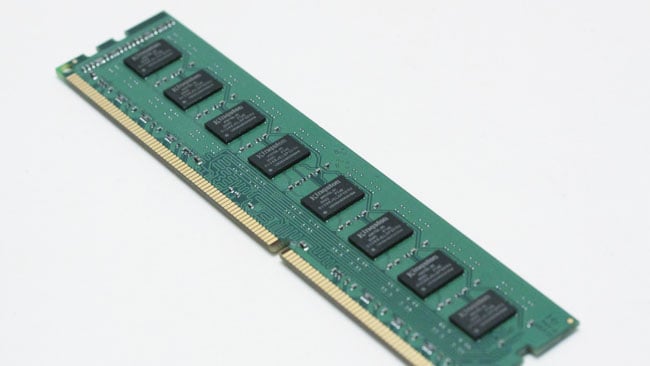

ECC memory usually has one more chip on it, for a total of nine rather than eight, but it'll be advertised as such

Speed

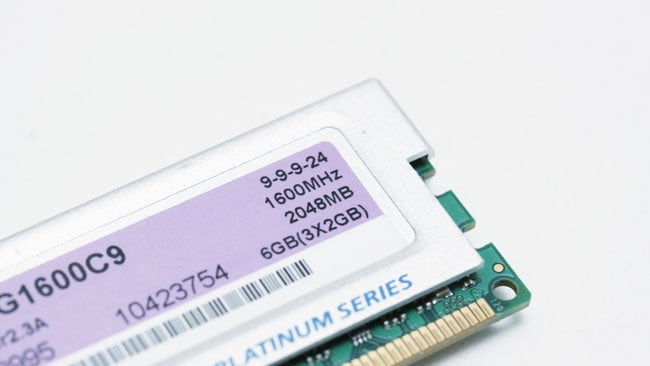

Finally, memory comes with a speed rating. This makes less of a difference than it might seem, as there are other factors limiting how fast things can be stored and recalled. Real enthusiasts will tweak low-level parameters called alarming things like “column address strobe latency” and “row address strobe precharge time.” That's an advanced topic, though, and buying the fastest memory the motherboard supports might net a few percentage points of performance gain at best.

If the notch in the module doesn't line up with the key in the slot, something is wrong

Memory modules are usually fitted in identical pairs, called dual-channel memory, or in rare cases in threes. It's usually sold in pairs (or threes) for this reason and usually, the memory needs to go in the right slots. If a computer won't start up, or if it thinks it has less memory than is actually installed, try shuffling things around in different slots – generally, the motherboard manual will indicate the order in which slots should be filled. Modern DIMMs may have 200 or 300 pins and a bit of fluff in a socket can cause problems, so blow them out with canned air (not by blowing into them, since your breath is, well, wet.)

Notches at each end engage with the latches, which usually close automatically when the module snaps home

Specifying memory is therefore simple enough – get the right type that goes as fast as the motherboard can handle. The only limitation is usually size, both the size of individual (pairs of) modules and the total amount. Since a motherboard will only have so many slots, it's natural to lean towards the largest possible modules so as to leave more slots free for future expansion. That can be slightly dangerous because some motherboards don't support modules above (or below) a certain size, so check the compatibility lists. This is less likely to be true on big Xeon or Epyc server motherboards, although those usually have many more RAM slots anyway, as they're likely to be used to create bigger, beefier machines that need more RAM.

The numbers separated by hyphens are detailed timing information, but this should usually be set automatically

Having discussed CPU, motherboard and memory, we've covered three of the four core parts of any computer. In fact, a computer with only these parts will generally start up and give a display, assuming we plug in a graphics card. It's unlikely to do anything very useful, however, until it can load some software from the sort of long-term storage that keeps its contents when the power is off. Next time, we'll look at hard disks, solid-state storage, and the choices that make the most sense in various situations.

Title image courtesy of Shutterstock.

Tags: Technology

Comments