Replay: When it comes to immersive film experiences, there is no doubt that the bigger the screen, the better. Roland Denning takes a magical mystery tour through the very first, true big screen experiences.

As we all know, screens, at least at home, are getting larger and camera and resolutions increase year by year. We could argue whether the growth in resolution is pushing the demand for bigger screens or whether the demand for bigger screens is encouraging broadcasters to up their resolutions, but the move towards larger screens is nothing new. The desire to go big has recurred throughout the history of cinema, but, generally, after a flurry of excitement, the industry settles back to more or less where it was before.

When we look back to the past at predictions, it was always prophesied that movies of the future will be increasingly life-like – bigger, more detailed and in three dimensions. It is as if we want cinema to be a window onto the world that we can step through, images that will fill our entire field of vision, so real that they can replace real life. This concept of aiming towards replica world, I think, is a fundamentally mistaken one. The language of cinema is sophisticated and complex. We switch points of view, we go from subjective to objective, we fly through space and time. It is a constructed world that has little to do with mirroring ‘real life’.

When science gives us images that are more detailed and ‘life-like’, filmmakers respond by making them softer, more mysterious or more graphic, to create spaces for our imagination to intervene. Cinema is not about reproducing the world, we don’t want to walk out into replica of reality, rather we want to be immersed in a dream. If big screens are the future, it is not about realism, it is about escape.

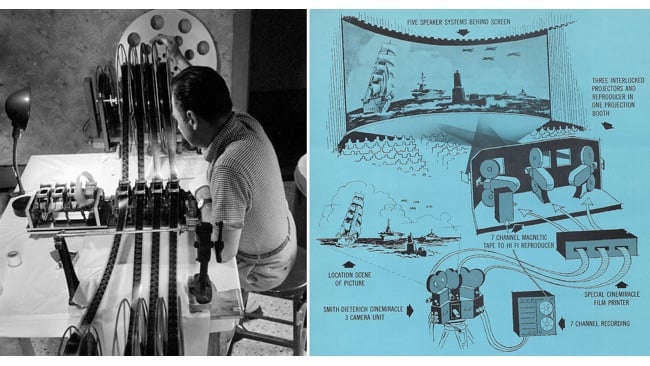

The Cinerama system

Cinema goes large to compete with TV

The great era for big screen cinema was, of course, the 1950s when the industry began to feel the threat of television. Although cinema had little competition in terms of the fuzzy, black-and-white TV picture (colour TV didn’t become mainstream until the late 60s and it would take another four decades for HD to arrive), the threat was real, and making screens bigger was one way to respond.

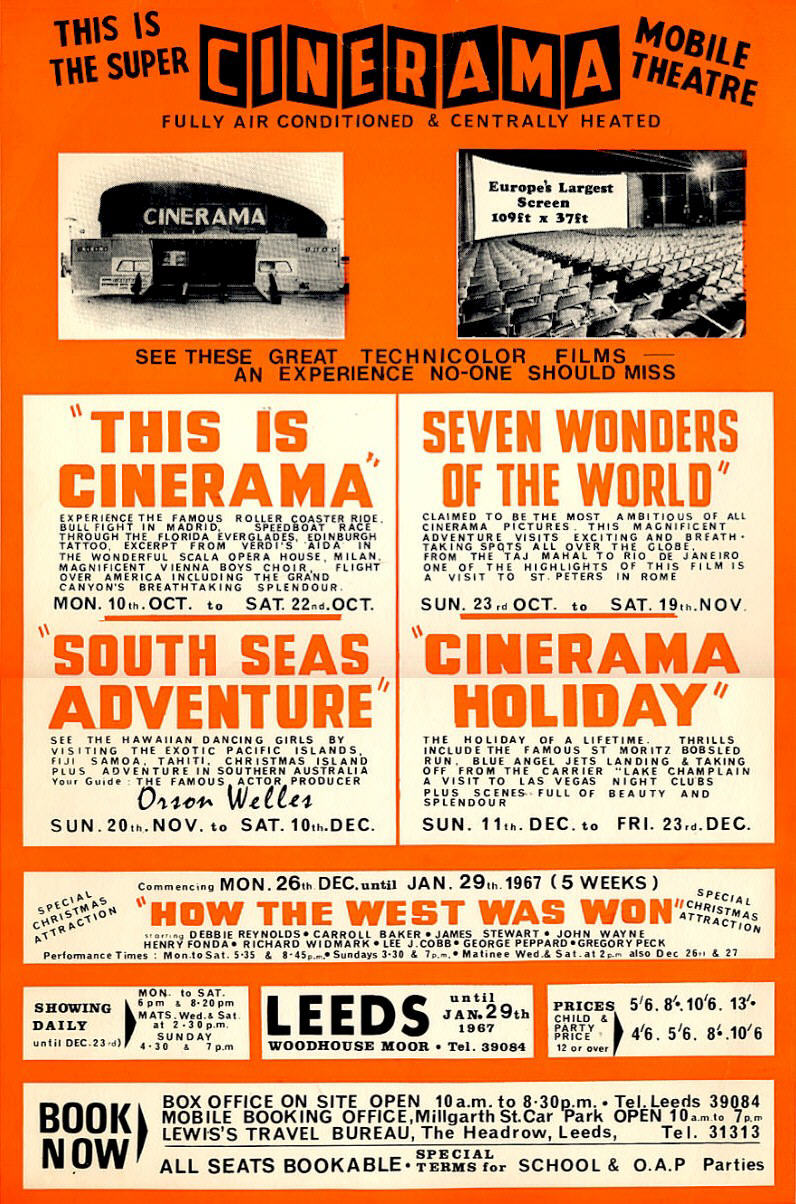

The most ambitious and biggest screen system was Cinerama, launched in 1952. Cinerama used three 35mm cameras, locked together, to be screened on three 35mm projectors. The screen was also curved at 146º so it would wrap around the audience. Synchronising three projectors, obviously, caused technical challenges and it was necessary to introduce vibrating combs to blur the seams between the screens. Not content with the complexity of installing the 3-projector system in existing cinemas, Cinerama also took their system on the road with a 110’ screen, a fleet of around 40 vehicles and a staff of 120.

Mike Todd, the producer of Around The World in 80 Days, introduced a competing system in 1953, Todd-AO, using a single 65mm camera and 70mm projector (the larger projection format allowed extra space for multi-channel soundtracks). Although some technical details would vary (Todd-AO, for instance, was initially 30 rather than 24fps) the 65/70mm, spherical (non-anamorphic) format, continues as the highest quality widescreen film format to the present day.

Cinerama had an aspect ratio of 2.65:1, Todd-AO and the 70mm formats that followed one of 2.20:1. Ultra Panavision 70 was an attempt at an even wider screen, using 70mm film and anamorphic lenses to produce an aspect ratio of 2.76. The last movie made in Ultra Panavision 70 was in 1996 until it was revived in 2015 for Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight (although only in the handful of cinemas throughout the world that had the projectors and lenses to show it). Post-1963, Cinerama abandoned its 3-strip process and used Ultra Panavision 70, and later spherical 70mm.

A poster advertising the Cinerama experience

Cinemascope

Cinemascope, also launched in 1953, offered a more practical solution. A wide format of 2.39:1 was achieved by using an anamorphic lens to squeeze the images sideways onto the film, then un-squeeze them in the projector. This obviously produces an inferior image to 70mm, but it enabled the same film stocks, cameras and projectors. Cinemascope was superseded by Panavision (confusingly, both the name of the format and the name of the camera manufacturer) who produced far superior lenses for the same format, and the ‘scope format remains with us to the present day. Interestingly, the distortions caused by anamorphic lenses are now seen as a feature rather than a flaw, and there is a nostalgic appeal to the ‘scope which goes beyond the shape of the screen.

So much for the 1950s. In the second part of this article, I will look at where we are today and what the future is for giant screens that fill our field of vision.

Comments