Long term problems? The condundrum of archiving digital films

Long term problems? The condundrum of archiving digital films

In for the long haul? The idea of archiving and keeping our digital data preserved for decades to come is a problem that most of us will be familiar with. Yet with no long term digital solution forthcoming, film studios are falling back to film technology, even for digitally produced movies.

Hands up if you know what Kodak's 35mm film numbered 2238 is for. Unless you're a specialist in film archiving and preservation, there's probably no reason you'd ever have come across it, but the existence of this specialist black and white film is related to the reasons that we now have a nearly century-old record of what the world looked like in motion. If we're going to create another hundred years of motion picture history, archiving is crucially important.

2238 is a panchromatic separation film, something we'll discuss in a bit, but it's essentially designed to last for a very long time and used by the likes of Disney to this day for long-term storage of their material. The fact that big film companies are still taking this sort of approach leads to some interesting discoveries about the history of colour photography and particularly of colour cinematography. With the odd esoteric exception involving exposing 2D barcode data onto film, more or less all serious digital archiving is done on tape, yet interest in film archiving persists. Partly that's because it's been proven to last a long time, but mainly, of course, because of the enormous amount of back catalogue that exists.

Scanned film can naturally be archived digitally, but Disney takes a belt-and-braces approach by recording film too

Film longevity

The longevity of film is, of course, not much more than a stroke of good luck. It was not designed to be an archival format. It was simply the only available technology, and the fact that it lasts well, or at least can last well when stored properly, is more or less coincidental. Even modern film is made out of gelatin (that is, boiled-down cow bones), stuck to plastic. Colour film (negative or otherwise) actually doesn't last all that well, particularly if it hasn't been washed very, very thoroughly to remove any remaining chemistry after processing. All film is washed, but very, very thorough washing takes extra time, and the problems don't show up for decades.

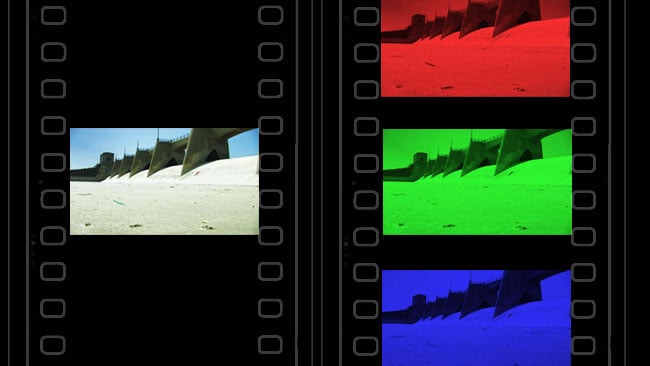

So yes, colour film can fade, usually towards magenta. The only colour films that don't fade are those which were acquired using the three-strip technicolor process, where the red, green and blue records are made directly onto three pieces of black-and-white film. That's where Kodak's 2238 film comes in; it's designed to take one of the red, green or blue records of something that's been shot on colour negative. The process is essentially duplicating one piece of film to another in an optical printer, just using coloured light and doing it three times, so that we end up with three monochrome records, each representing one of the red, green or blue channels.

Full colour image

In negative, the separations become cyan, magenta and yellow masks rather than RGB - but the principle is the same

The blackness of dense areas in a black and white film are made up of tiny clouds of metallic silver particles. That's what gets bleached out of colour film during that stage of the processing, and that's why tricks like bleach bypass make colour negative look dense, because it leaves the opacity of metal in the exposed areas (usually on an interpositive, so the result is “darker”.) Processing companies often recycle the silver from their bleach step, but it stays in black and white film, so it doesn't fade. By comparison, the darkness of a colour film is made up of clouds of dye, which can continue to be affected by both light and any remaining chemicals.

So, black and white film doesn't fade, but it can still shrink. The base of the film, which is a strip of plastic, is fairly stable, but the gelatin can dry out. Worse, because the plastic doesn't shrink while the gelatin does, the film can end up curved, dished, or worse. If a piece of film is completely unreadable, that's usually why. Shrinkage can be almost entirely avoided by storing the film and the proper temperature and humidity, which is where we get the idea of storing valuable film down a salt mine where, in at least apocryphal cases, the cool, damp air is ideally suited. The issue of shrinkage is why at least some modern archival film scanners keep the film in continuous motion over rollers without the intermittent stop-start action of a conventional camera or projector mechanism. Continuous motion deals better with (slightly) shrunk film.

The Cinesave system, shown a few years ago at IBC, stored digital information on black-and-white film

Keeping things together

The need to keep three pieces of film together is naturally a recipe for disaster, and the final trick is to expose the red, green and blue records sequentially onto the same piece of black and white film. The first people to do this were probably – again – Disney, or another animation company, in the earliest days of colour when they wanted to produce animation in colour for use with the Technicolor printing system. Rather than have a (rare and expensive) three-strip camera on the animation stand, they'd simply expose three frames sequentially, through colour filters, onto monochrome film stock. That way, everything's kept together, and if there is any shrinkage during storage it will affect the three adjacent red, green and blue frames more or less equally, reducing the chances of misalignment.

Given black and white separations, then, we have a record of a film which can stand the test of time, to the extent that it's even being done for newly produced material – even for Disney films which have never seen the inside of a camera, digital or film, to begin with. It was certainly done for Star Wars, which is why the modern restorations look so good. It isn't a perfect solution, though; naturally, anything exposed onto film suffers at least a little degradation in sharpness and added grain. Film stocks such as 2238 have low sensitivity by the standards of stocks intended for use in cameras. This is fine, because optical and contact printers can fire a comparatively enormous amount of light into the film compared to the light cast by a camera lens. When people have loaded 2238 into stills cameras and taken photos, it works out at around 25 ASA, but naturally enjoys excellent sharpness and low grain as a result. Nevertheless, some productions have used the faded colour originals combined with colour separations in pursuit of the best possible combination of sharpness and colour.

There's no way to archive film that perfectly captures every grain digitally

Creating colour separations is, of course, expensive, but it is known to work. We don't really know how well LTO tape will last – the manufacturer says decades, but there's not likely to be any way to hold them to that in the year 2047. Digital archiving can achieve losslessness in a way that analogue can't, of course, although there's then the argument as to whether we're losing anything by scanning a film original, even at a sufficiently high resolution. It's a complicated subject, but archivability remains a powerful argument for the film purist.

Title image courtesy of Shutterstock.

Tags: Production

Comments