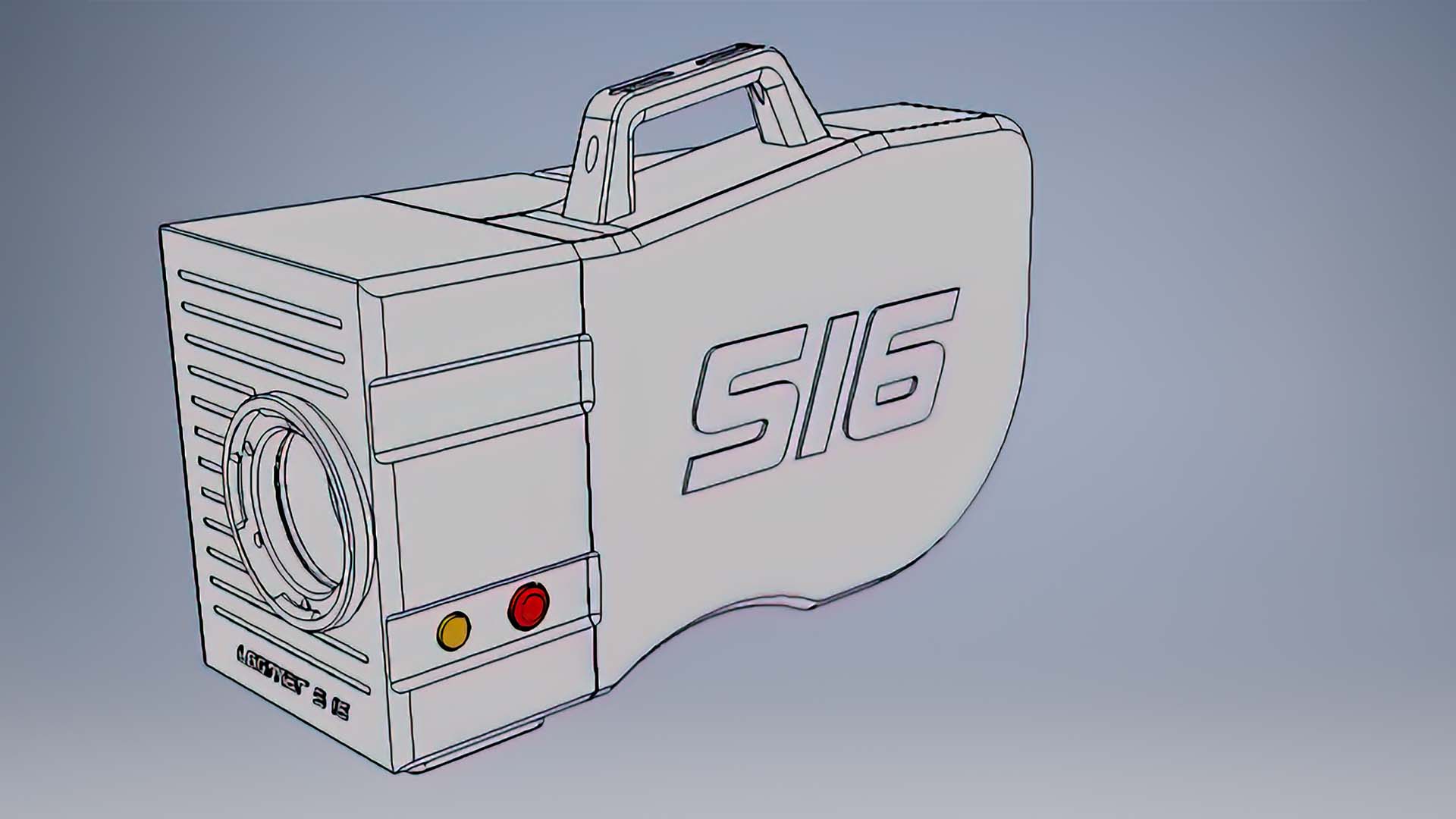

Logmer has stated its intention to release a S16 film camera some time this year.

Given the splash achieved by Logmar with its Magellan 65mm camera, it's easy to forget that the company's background includes a lot of work in much more modest formats. Its Chatham Super-8mm camera has been described as the first really new option in several decades, and now there's a (CAD model of) a S16mm camera on the website.

Background

Much as it's great to see new equipment emerging, the implications of all this for photochemical origination in general are interesting - and not just because it's a vote of confidence in the format. The practical value of this is that while film itself has some popular capabilities, the devices which use it can sometimes leave a little more to be desired. A lot of Super-8 cameras, for instance, are deeply, deeply primitive, with feeble viewfinding, zoom lenses of extremely dubious quality, and ergonomics that seem to assume humans have the ability to arbitrarily develop additional elbows any time it's convenient.

Modern audio recorders tend not to interface easily with 1960s and 1970s technology, which immediately increases the required crew to include someone to record sound, and in the end, a lot of Super-8 cameras don't even perform particularly well as cameras, being very heavily reliant on modern digital tracking and stabilisation technology to achieve reasonable registration. Watch the sprocket holes rhythmically bouncing around in footage that's been stabilised to the pieces of fluff at the edge of frame, and while it's hard to tell where these problems really begin it's easy to get the impression that even the film wasn't made that carefully in the first place.

There are Super-8mm cameras which do better at all these things, particularly options which can mount better, often C-mount lenses. Those cameras are rare and expensive, though, and becoming rarer and more expensive as more of these decades-old pieces of technology inevitably encounter their MTBF. What's less intuitive is that a lot of these problems are also experienced by machines at the other end of the scale. There were never that many 65mm cameras, even if we're talking about more conventional 5-perf 65mm as opposed to the 15-perf insanity of IMAX, and not many of those 65mm cameras were particularly convenient from the point of view of the modern cinematographer.

Naturally, 65mm machines don't suffer the instability of the tiny Super-8 frame, both because the negative is larger and because the cameras are - to put it mildly - not designed or built to a consumer pricepoint. There's a Super Panavision 70 camera standing in the lobby of the company's Woodland Hills rental facility (or at least there was, pre-pandemic) and it's immediately clear why it's become largely ornamental. It'd be interesting to see if it's leaving dents in the concrete floor, but to figure that out would mean moving it, and that's an ambitious goal for anyone without a team of beefy grips and a construction crane on hand. The company's much saner and more recent Panavision Large Format System 65, introduced in the early 90s, has more of the conveniences a modern crew might expect, but it's still an absolute beast (and confusingly named, given what "large format" now means).

Arri's 765 is perhaps slightly more svelte, but Logmar's Magellan is almost certainly the handiest 65mm camera ever made - and of course, being a design of the twenty-first century, it has a lot of the niceties a modern, Alexa-trained crew might prefer to have, including wireless features and a bright, easily-visible electronic viewfinder. I know, we like optical viewfinders - pipe down at the back - but look at the sheer petiteness of the thing. You can handhold it without risking the need for some sort of gruesome orthopaedic intervention afterwards.

Super 16mm

So, Logmar's work to date seems very worthwhile in the context of general film camera technology. Whether that turns out to be the case for the new 16mm design remains to be seen, not least because we can't load stock into a CAD model. Certainly the potential is there. Many of the 16mm cameras used today are almost as primitive as, and often older than, the Super-8 options which are currently tearing up eBay. Demand something as every day as a reasonable-quality video tap, high speed, and, particularly, noise levels compatible with recording sound, and you'll quickly become aware that Arri SR3s have maintained their value shockingly well even though most of them don't even have HD taps. The new design is intended to shoot up to 48fps in a pin-registered gate with 3G SDI viewfinding outputs that the company describes as "focus critical." No mention is made of sync sound compatibility.

Whether or not we agree that Super-16mm can outresolve a 1080p video stream (it possibly, barely can with slow stock, good lenses and a careful scan), it'll certainly look better than Super-8. Well, of course it will - why is that even worth mentioning? Because it's not that hard to make 16 actually look cheaper than 8, which shouldn't be the case but really is. One three-minute roll of 500-speed film in Super-8 format retails for a slightly alarming £44 and runs for three minutes. At least some prices for ten minutes - four hundred feet - of 16mm stock suggest it's potentially cheaper per minute. Processing may vary but scanning is often priced per frame regardless of the gauge.

So, much as 16mm has long played second fiddle to 35, Logmar's camera should certainly make it easier to get the best out of the format. The company has stated its intention to start taking pre-orders this year.

Tags: Production Cameras Film

Comments