Replay: If your idea of a budget is whether you can afford a bacon sandwich for the crew, you probably can't afford a proper soft light. So here's some suggestions about what you can do, true guerrilla style.

Most of the lights that’ve ever been made in the history of filmmaking have been hard lights, and if we wanted soft light we’ve had to bounce that light off something, diffuse it through something, or even both (see “book lights”).

What we call a soft light depends, of course, on the relative size of the light and the subject and the distance between the two, but it wasn’t until the great Frieder Hoccheim figured out how to create fluorescent tubes that didn’t make everyone look recently exhumed that the film industry really had much access to devices that actually emitted soft light, even if only in one axis (yes, there were scoop lights, but those are really just a hard light with a built in bounce surface.)

Since then people have tried all kinds of techniques to create direct-emission softlights. The first device ever to bear the Skypanel name was actually a flat panel xenon discharge device of a type that’s rarely been seen elsewhere. There was actually a tease of a competitor, but the technology was ultimately subsumed by LED.

LEDs, of course, are strictly speaking also hard light sources, since the largest of them has an active area only a few millimetres square, but their development has been characterised by nothing more than a desperate rush to create high power hardlights by packing as many of them as possible into a small space. Spreading out the bright dots into a field is easy and does a reasonably good job of emulating a softlight, even if we don’t then diffuse the result.

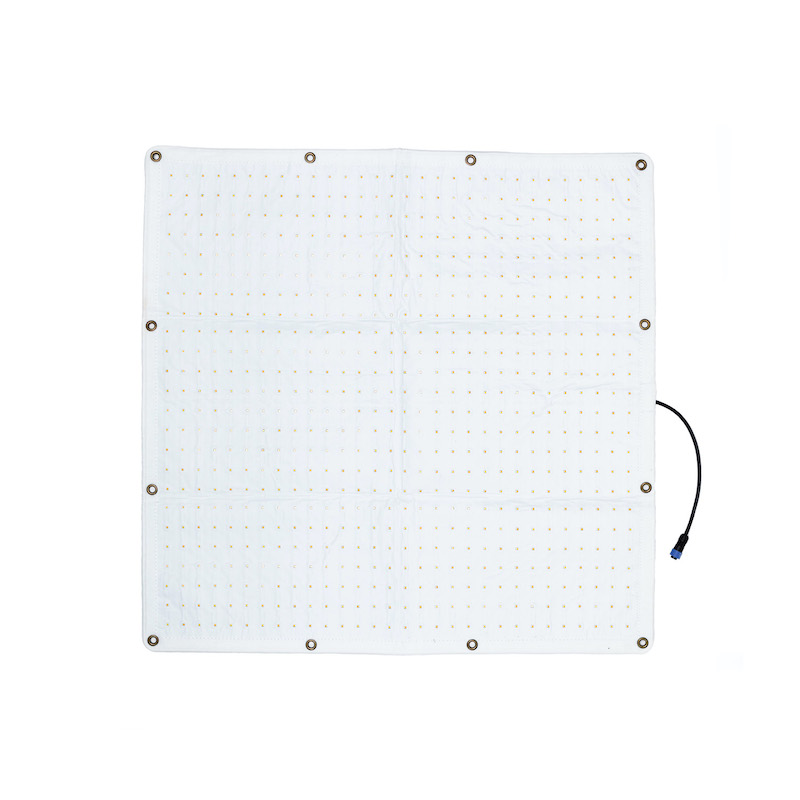

The Aladdin Fabric Light.

Aladdin Fabric Light

That’s exactly what something like an Aladdin Fabric Light does. Each panel is a hair under three feet square and contains 720 LEDs, drawing about 200W. That sounds reasonable, then we realise that it’d be quite reasonable to zip-tie anything up to sixteen of them together, using the eyelets thoughtfully provided for the purpose, to create a twelve-by-twelve frame of dimmable, variable colour temperature soft light dissipating 3200W.

That’s a lot for such an efficient technology, certainly more than could be achieved by anything other than the most powerful hardlights fired through diffusion. The real benefit, though, is that this sort of thing can be rigged very quickly, moved very easily, and takes up vanishingly little space compared to the fresnel-plus-diffusion approach.

Of course, one Fabric Light panel lists in the UK for an ambitious £2632, so building that light would cost more than forty-five thousand pounds after sales tax, but there are other approaches.

The inexpensive way

Cheap ways to soft light begin with directing tungsten-halogen (not LED) work lights at polystyrene insulation foam and go up from there. A 500W linear floodlight has nothing like the output of even a single Aladdin panel, but it’s long been a favourite approach under circumstances where time and power (and air conditioning) are cheap but gear is in short supply. Regrettably it’s becoming harder to find proper tungsten-halogen floodlights, but they are vanishingly inexpensive, flicker free, hot-start, dimmable, and have near ideal colour quality.

A true halogen worklight. Not easy to find these days. Image: Shutterstock.

While at the home improvements store, get some of that behind-the-radiator foam with the reflective coating, for a higher gain reflector, or paint the polystyrene with a pale colour to create interesting tint effects. The “Mint Macaroon” shade from Dulux’s EasyCare Kitchen range creates something akin to the steel green we’re supposed to believe looks like moonlight in 2020. You can get it in little tester pots, a couple of which will cover a bit of polyboard, but, obviously, tell everyone it’s calibrated Cinechrome Reflector Coat and charge accordingly. I mean, it is pretty calibrated.

Improving performance

For massively better performance for a slightly higher price, drive it with fluorescent tubes. Other than in really large numbers at really close range, fluorescents don’t really count as soft light, but they can be bounced and their broad coverage makes for compact setups, as they can be placed closer to the polyboard. It used to be a good idea to get fluorescent work lights and replace the tubes with a high-CRI option, although real Kino-Flos are now sold cheap by people moving to LEDs, so it may be worth looking into that if all the worklights at your local DIY store are now blue, miserable-looking LEDs suitable only for scenes titled “interior mortuary refrigerator.”

If you really must have the latest technology, there are now a lot of people selling LED soft lights, because LED soft lights are not particularly hard to make. Most of them are also not really big enough to be considered very soft lights; the one-by-one-foot panels that people spend their student loans on are still probably too expensive and too heavy to be rigged into, say, a four-by-four configuration. They can be bounced, of course, but that’s a pretty inefficient way to further diffuse an already-large lightsource.

If in doubt, buy a shower curtain (without fish on it)

At this level, most people can probably afford proper diffusion, but if not, it’s always possible to go to the place that sells toilet brushes and get a shower curtain, which has been the last refuge of cinematographic scoundrels since a time when it was really bad idea. Shower curtains, staple-gunned to a wooden frame and put in front of a hot tungsten-halogen lights, are likely to melt, drip and cause people below to run around shrieking, but they’re much more practical now, in a world of LED or fluorescent.

This could be your next film equipment purchase... Image: Shutterstock.

Most people are familiar with shower curtains, but they come in fairly solid white which can be used as a bounce or very dense diffusion, or more frost-like effects which allow the light to retain a degree of directionality. Try to get one that doesn’t have little blue fish printed down the edge or people will ask awkward questions.

At the other end of the scale, companies such as Lee and Rosco have many kinds of very clever diffusion that will achieve significantly higher efficiency than a pocketmoney sheet of textured plastic. Rosco’s Opti-Sculpt, which we looked at previously has rather higher efficiency than even proper conventional diffusion, albeit at a cost. It could be used to create soft light.

In the end, it’s worth reiterating that even the meaning of the phrase “soft light” depends on the size of the light source, the size of the subject, and how far one is from the other. Sometimes, a softbox on an LED hardlight is all that’s needed. Other times, only one of those studios with the permanently-installed forty-by-eighty white bounce that’re use for car commercials will do. It’s probably possible to make one of those out of bathroom accessories, too, but probably a bad idea to suspend the result over a Lamborghini.

Tags: Production Tutorials

Comments