The man behind groundbreaking visual effects in films such as Blade Runner and 2001, Douglas Trumbull, has passed away aged 79.

It's traditional for the first sentence of an obituary to summarise the achievements of the deceased, but Douglas Trumbull's achievements ranged so far and so wide, across such a huge range of disciplines on such a huge range of films, involving so many famous and beloved projects and people, that almost any enumeration of his achievements will inevitably beg the reaction "but what about..."

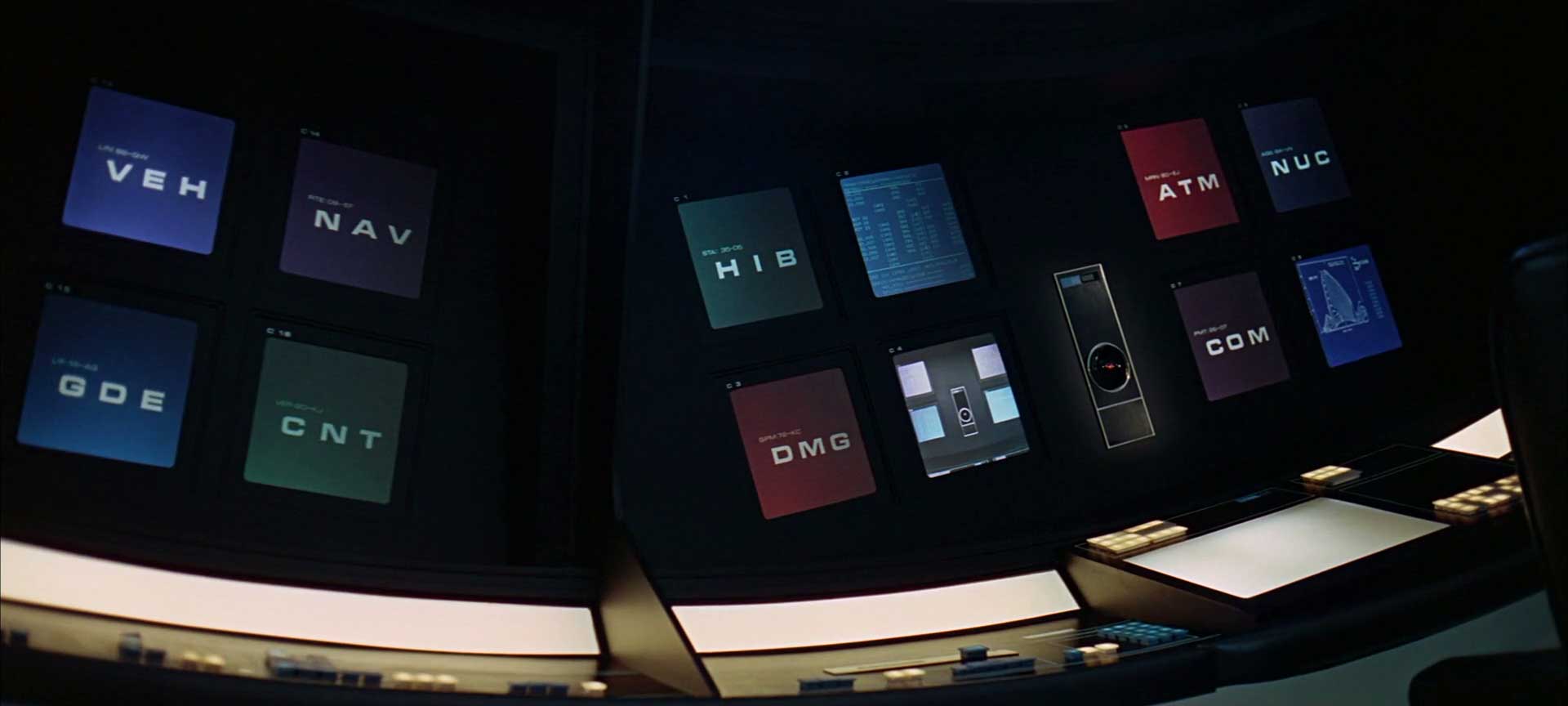

Let's put it this way: this is the man who turned down Star Wars, for better or worse. Trumbull's involvement with technology began in a way that will be familiar to many people: a childhood spent tinkering, formatively, at home. His prodigious professional life began in the 1960s, when Trumbull was in his early twenties, working with Kubrick on 2001: A Space Odyssey, to create the screen display graphics.

Display graphics in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The fact that nobody, including Kubrick, had really worked out what a "stargate" should look like meant Trumbull quickly found himself promoted to the position of interdimensional rift architect, pioneering the technique that would be known as slit-scan, producing something that looked appropriately unlike anything anyone had ever seen before. By the time The Andromeda Strain was in production, Trumbull had returned to Los Angeles and set up his own company; he recapitulated many of the techniques of 2001 to create pseudo-digital display graphics using decidedly non-digital techniques.

In 1971 he directed Silent Running, a movie adored more now than it was at time of release. Trumbull's in-depth knowledge of the craft techniques behind spacecraft-bound science fiction movies gave it production value far, far beyond its comparatively minuscule $1M budget. It might have seemed, then, that Trumbull was destined to direct again, although he found himself (largely, it seems, through nothing more than repeated misfortune) stuck on a lot of projects that perpetually almost happened, and eventually took more visual effects work putting together bluescreen composites on The Towering Inferno.

Let's be fair: when your backup plan is The Incredibly Financially Successful Towering Inferno, you're probably doing something right.

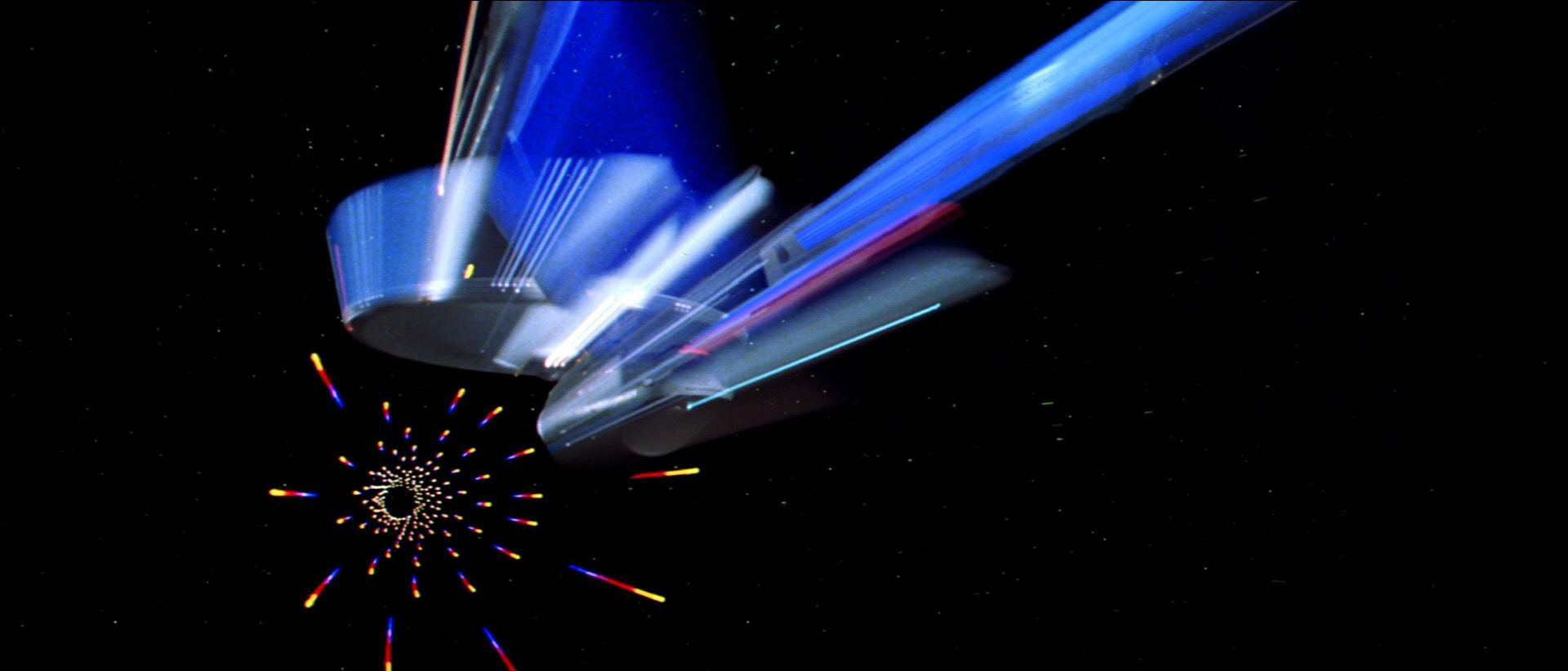

The Starship Enterprise enters warp speed.

That was the point at which Star Wars came knocking, although Trumbull was busy; the result was a key formative experience in the creation of Industrial Light and Magic, so the circumstances might be seen as serendipitous in the end. It didn't stop him becoming involved in Close Encounters of the Third Kind and then Star Trek: The Motion Picture (reuniting with Andromeda Strain director Robert Wise), in both of which films aficionados will recognise the streak-generating techniques Trumbull developed with Kubrick a decade earlier.

Showscan

Trumbull had always been an inventor, creating many of the devices required to produce the work for which he became most famous. Post Star Trek, though, was when he began to push for improvements to the fabric of cinema itself with his Showscan process, which was intended to use 65mm negative at 60 frames per second. The clarity of Showscan was naturally enormous, although Trumbull wasn't able to use it as planned on his second feature as director, Brainstorm.

High frame rate acquisition - much easier now than then - has since suffered a very mixed reception, although Trumbull's experience with it would lead to work on theme park ride films including those at the Luxor hotel in Las Vegas and the Back to the Future ride at Universal Studios Hollywood, which ran until 2007. In these situations, the clarity of high framerate makes more sense, creating more convincing windows onto an ersatz reality. Via this avenue, Trumbull was, at one time, a director of IMAX.

Trumbull kept pushing new ideas into his 70s, and as late a 2016 (at the age of 74) he was quoted by Science and Film magazine as planning another feature. His last credit as visual effects supervisor was on 2018's The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then the Bigfoot, although a glance at his IMDb reveals the mixed, portfolio career of a renaissance man, or at least a man in the renaissance of his field.

Naturally, one does not experience a career like that without receiving some recognition. Trumbull was nominated for three Academy Awards and eventually received the Academy's honorary Gordon E. Sawyer Award, alongside the Visual Effects Society's Georges Méliès award in 2012. He was honoured by both the American Society of Cinematographers with their Lifetime Achievement Award and the SMPTE twice, including with the Society's prestigious Progress Medal. He was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2010.

From the glowing production history to the technical progress and entrepreneurship, it's almost impossible to overstate Trumbull's contribution. His work more or less charts the technical progress of film and television production during the latter half of the twentieth century, such that more or less anyone who has any interest in screen imaging will have been affected by his artistic or technical output.

Douglas Hunt Trumbull was born on April 8, 1942, and died 8th February 2022. He was 79. Trumbull's daughter put out this post on Facebook.

Last year RedShark published what could possibly have been one of Trumbull's last ever interviews. You can read it here.

Tags: Post & VFX News

Comments