With the recent passing of Douglas Trumbull, here's another chance to read our interview with him, published last year.

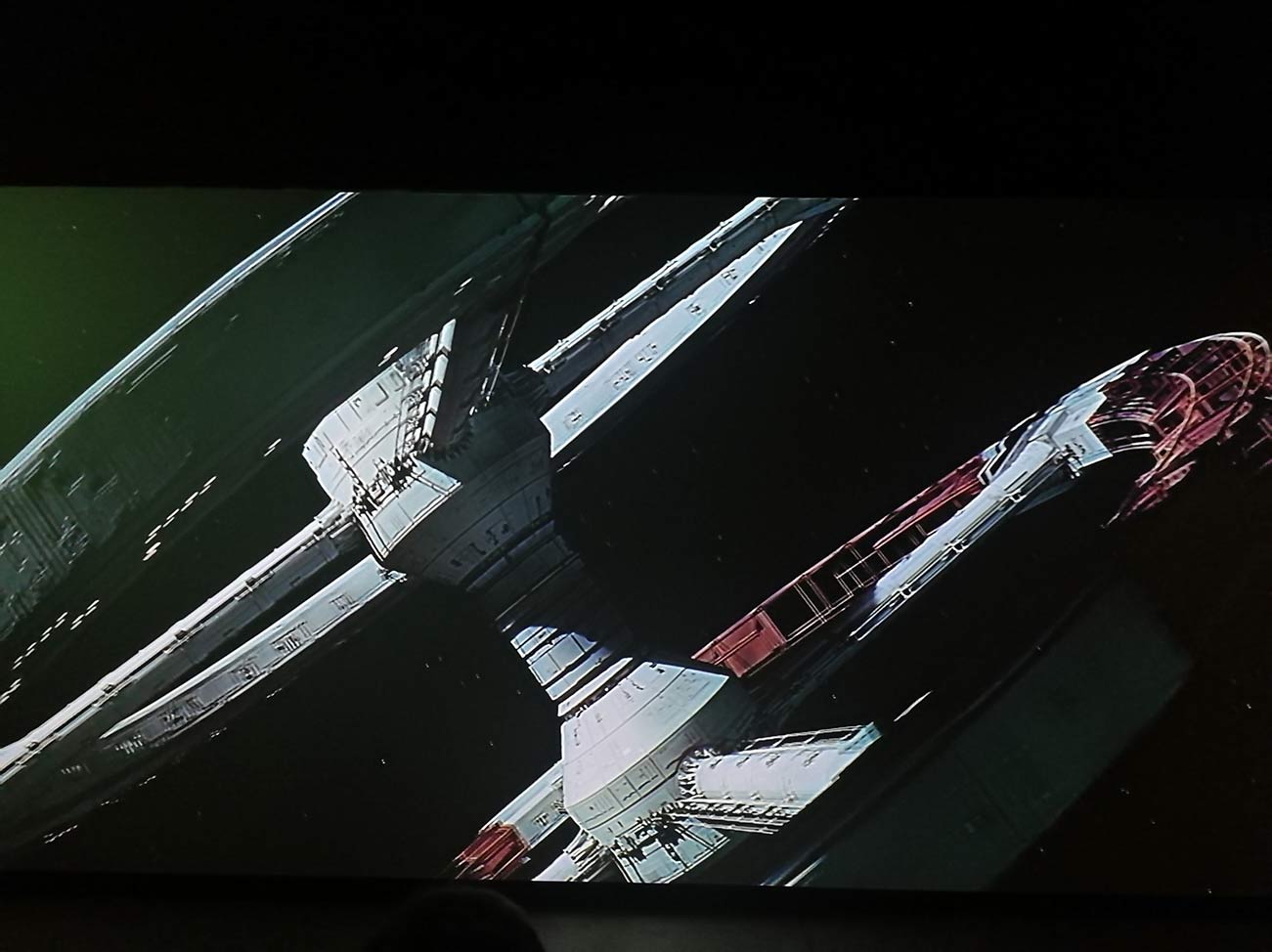

The Star Gate sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey, one of the most iconic, visually stunning and hallucinatory moments in cinema history, is being revisited in a new film by its special effects creator Douglas Trumbull.

Trumbull created the kaleidoscopic space-time travel sequence for director Stanley Kubrick and plans to “update” the effect for an “epic sci-fi adventure” he plans to direct.

The project is in early development but Trumbull revealed the outline of the film’s plot and his reasons for returning to the director’s chair 38 years after making Brainstorm to me at the Makers Pop-up conference.

“It’s not just about Jupiter [which was 2001’s destination] but way beyond that,” he said. “It’s about going to another star so the distance that has to be traversed is vast. The whole issue of travelling through space is going to be a little clearer that it was in 2001.

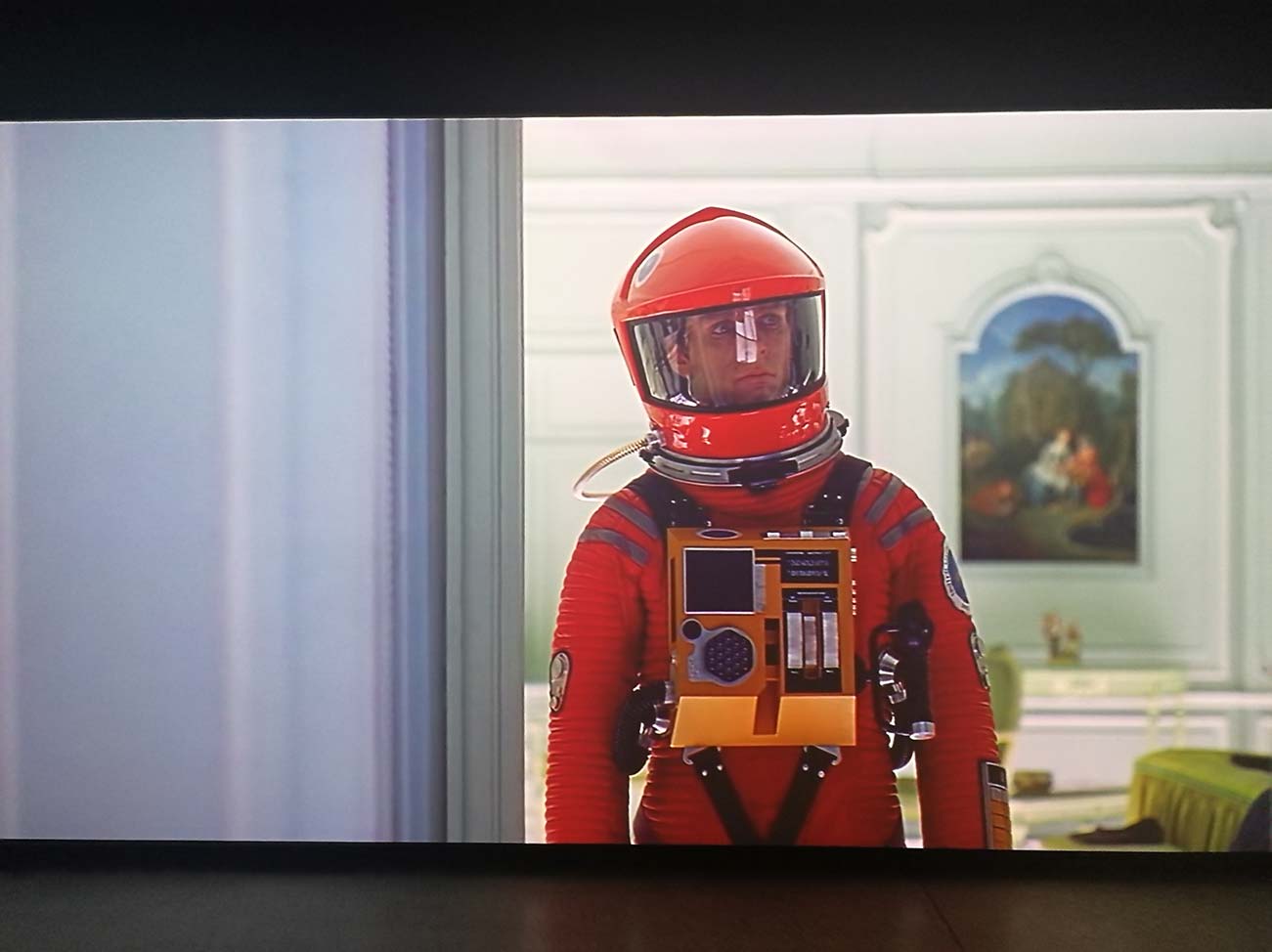

“2001 was oblique in the way the story was told,” he added. “[The audience] has to do a lot of interpreting to figure out what Kubrick was trying to say to us about the evolution of mankind and what it means to be human. The Star Child went over [many] people’s heads [but he] was trying to tell a deep and profound story about man’s place in the universe and about making contact with intelligent aliens.

“I am trying to touch on those themes in [my] movie. I hope I can manage to make my two worlds collide – that of trying to make this film in the new medium and to tell it in a new way.”

Trumbull was 23 when he devised the slit-scan technique to meticulously build the Star Gate sequence at Shepperton Studios. The method was accomplished by filming thousands of images of, among other things, architectural drawings, printed circuits, and electron-microscope photographs of molecular and crystal structures as well as coloured paints and chemicals shot in slow motion in a dark room.

Now Trumbull is working with Epic Games to bring his new vision to life.

“I’ve been working on blending CG with practical effects for over thirty years,” he says. “I am presently applying Unreal Engine to a virtual set for this feature film. Not that I won’t occasionally use miniature or more organic effects but the wonderful thing that has occurred in VFX is we can now do very effective photoreal environments for movies - maybe even characters - in realtime so there is a genuine interaction between [the virtual] and the live actors.”

The new project is a deeply personal one for Trumbull in many ways. Not only does he credit Kubrick with changing his life but with essentially attempting to reinvent cinema as a big screen (70mm) spectacle. In the years since A Space Odyssey’s 1968 release, Trumbull feels Hollywood has gone backwards, failing to understand what Kubrick had achieved, and now fatally dominated by “small screen” thinking for movies destined for streaming online.

Trumbull has made it his mission not just to educate Hollywood about the potential of cinema as he sees it but actually inventing a whole production and exhibition format to deliver on the promise.

MAGI

In recent years he has promoted MAGI, a filmmaking format that captures in 4K resolution, stereo 3D and high frame rates. He has coupled with this with MAGI pods which are pop-up cinema screens designed to exhibit widescreen movies at 4K 3D HFR and even has an economic model worked out. For more on this see here and here.

The most contentious of these parameters is high frame rates with which filmmakers like James Cameron, Peter Jackson and Ang Lee have failed to convince audiences.

Trumbull believes high frame rates essential for giving audiences a “hyper outer body experience" which take you beyond the limits of a TV screen and becomes totally immersive.”

However, he believes no-one has yet presented a HFR movie in the right way. He believes the soap-opera video quality that critics see in movies like Gemini Man can be rendered ‘cinematic’ by introducing a shutter into the projection process.

“Very few people in Hollywood understand how movies work,” he says. “They aren’t aware that in all the digital projectors installed there are no shutters – there is no flicker. [Yet flicker] is what differentiates movies from TV. So, if you introduce digital flicker in the projection of the film [actually in the DCP file] it can look fully cinematic even if you raise the frame rate to 120 or 160.”

High frame rates + shutter

Increasing framerate reduces blur and improves the temporal continuity of motion, he says, making cinematic experiences “much more exciting and stimulating by virtue of the medium itself.”

He says he came to this conclusion only recently. “The shutter is so simple and so elegantly part of what cinema is supposed to be that if you make sure a shutter [happen] during the screening of your movie you can increase the frame rate to anything you want it to be.

“Most people in exhibition, the production community or studios are not aware that all those digital projectors in cinemas today are running at 144 flashes a second. Just to show a 24fps movie we are repeating the frame 5-6 times with no shutter. The potential for HFR is already built in to the industry. All the tools to upgrade the industry are already in place.”

He plans to set up a demonstration centre in LA to get his technology closer to decision makers including SMPTE, production heads, cinematographers and directors.

“I’ll say this is what we can do now, all the elements are here and available. We don’t have to build anything new.”

Nonetheless he is pessimistic about convincing executives. “The movie industry is glacially slow to change,” he says. “It is really disturbing to me that the whole issue of high frame rates is upon us now in a way it was not possible before to achieve before.”

He says it is in studio’s own best interests to up their game.

“The studio is paying for all the costs of film production - the sets, the locations, the equipment, the actors and crew - but the medium itself is only delivering a small percentage of what they are paying for. Upgrade the medium and upgrade the theatre and you get a much better experience and much more value for money.”

Most directors he says are not even interested in making an epic picture for the giant screen in the manner of 2001 or Lawrence of Arabia, with a few exceptions.

“Chris Nolan is one of them who is a real advocate of giant screen. Whether Interstellar, Dunkirk or even Batman he has used IMAX cameras and gone the extra mile to make IMAX prints of his films. I laud him for that.”

His Showscan technique made billions for Universal Pictures in a Back to the Future theme park ride that he describes as achieving “a super-intense kind of virtual reality.”

He is less enamoured though of VR head-mounted displays as a storytelling media.

“It’s a director-less medium in many ways,” Trumbull says. “[Even] if Kubrick had said ‘come on board my space station and look around’ you wouldn’t have any plot structure or story involvement in any fashion. I am not very intrigued by it.”

New cinematic immersion

After making short demo film UFOTOG a few years ago in his MAGI formula, Trumbull feels that making a whole feature length movie is the only way to prove to the industry the future it is missing.

The idea, he says, grew out of the looking back at his career and asking “What can I do which will be as good if not better than things I’ve done in the past?”

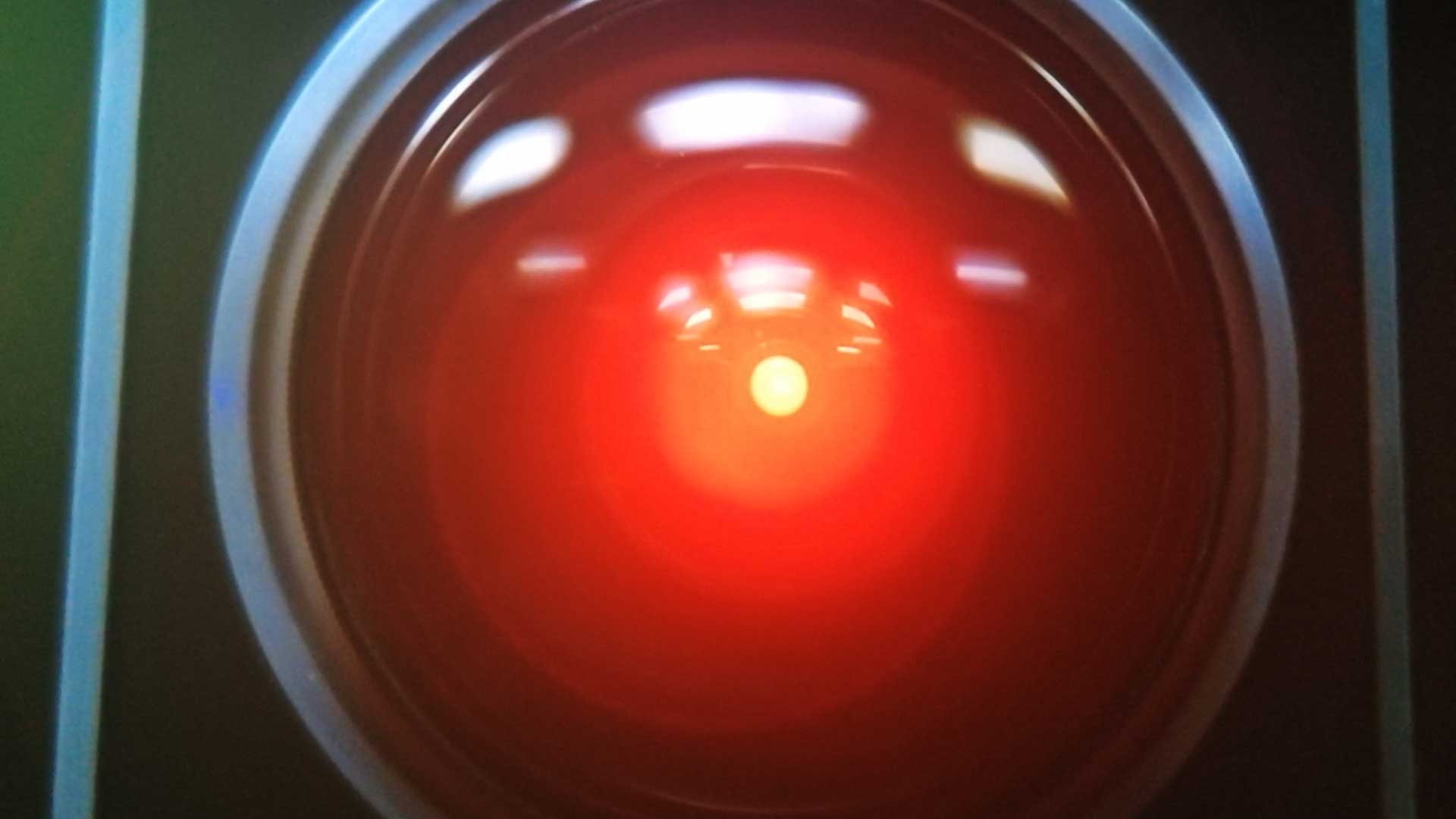

“My experience working with Stanley Kubrick was a complete life changer for me and a game changer for my perspective on cinema. He was my film teacher and 2001 was my film school. I am proud I was able to bring to 2001 a lot of latent skills I didn’t know I had to do all the animated HAL read-outs, and Star Gate and Jupiter. I’m proud of helping Stanley achieve his vision for a movie that still stands out as a unique piece of cinema.

“From my perspective the industry has been going downhill ever since and moving away from giant screen 70mm and the cinematic language he was delivering.

“Kubrick was trying to pave the way for a new form of immersive cinema and most people didn’t realise it. I’m trying to do it again with this film.”

Tags: Production Featured Interviews

Comments