Replay: The Linny LUT by TheBrim is certainly the priciest LUT we've seen. But what's the science behind it, and can a LUT really emulate the way a photochemical process works?

People have been using electronic processing to make images look (in their opinion) better for quite some time. The process used by the Filmlook company was developed in the late 80s and deployed in broadcast television in the early 90s, and lots of software has been released that tries to do similar things since. The technologies change and in 2018 there's a push not so much for a film look as a high production value look, albeit informed by decades of photochemical history.

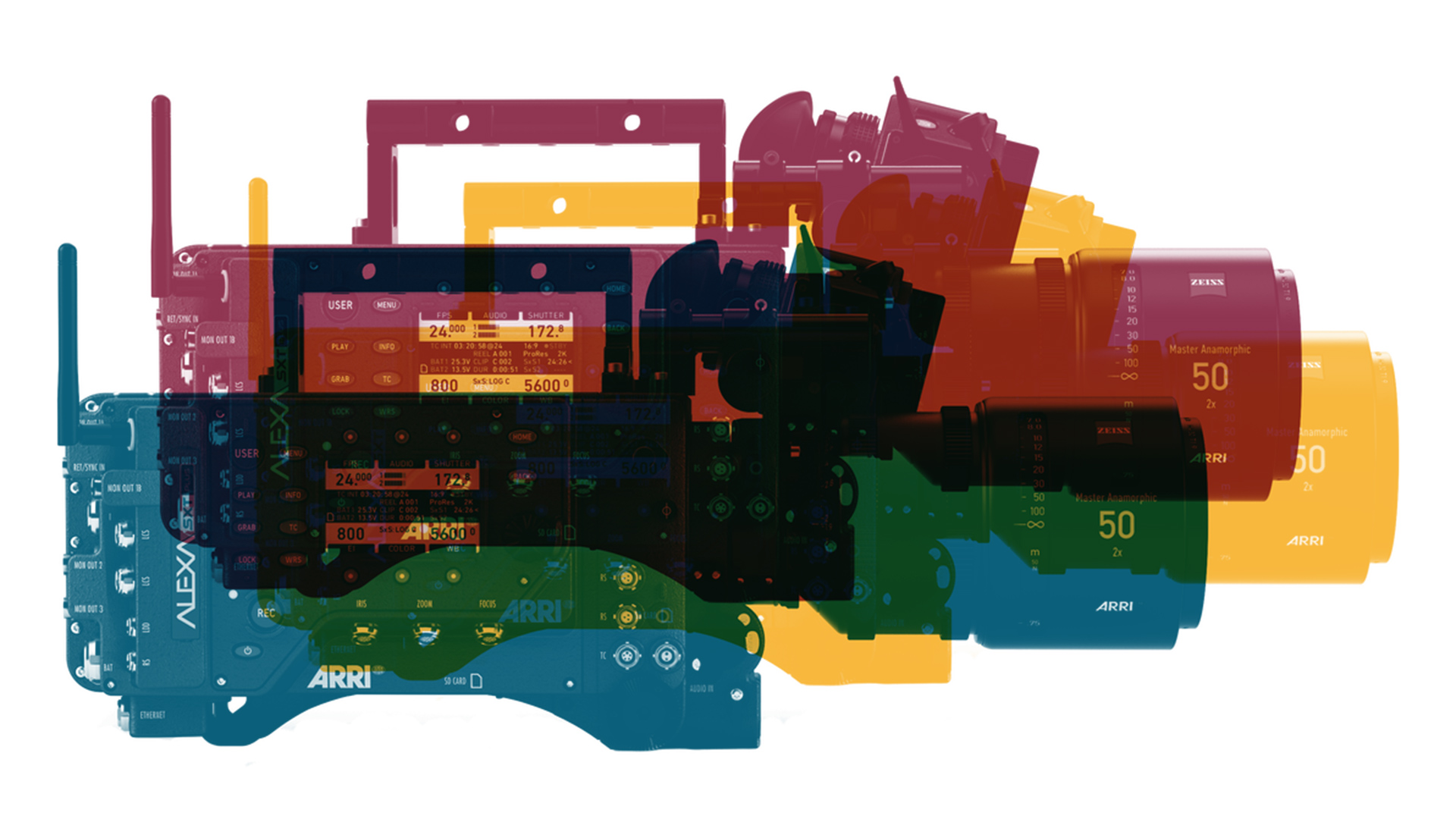

As such, when an organisation promotes the idea that it is influenced by the characteristics of film, it isn't doing anything new. What I'm talking about is something that Croatian organisation The Brim refers to as “a new era of ARRI Alexa Color Science”, implemented as a set of lookup tables intended to do a better job than the Rec. 709 conversion suggested by Arri. There's much reference to the way that photochemical photography works, which is not controversial. Modern cameras are not expected to rigidly observe the expectations made by 709 and 1886, so there's a lot of opinion involved.

Pricing

The controversy seems to arise from the pricing. At $370 for a single LUT or up to $777 for the most comprehensive set, this has to be among the most expensive colour cubes ever. Anyone charging several hundred dollars for LUTs needs to have a good justification for doing that.

The technical discussion is long on interesting ideas and short on specifics. The idea is that photochemical film is a subtractive medium. The layers in film aren't red, green and blue; they're complimentary of those, so it starts off clear and then combinations of cyan, magenta and yellow are used to block light.

It's often said that subtractive mixing will tend toward higher saturation at lower brightness, because the more light we subtract from something in order to add colour, the darker it will get. That's not quite the whole story: use a magenta filter to subtract 100% green from white and we have a fully saturated, full brightness magenta. Add 100% red and blue to black and we have the same thing. On paper, things are pretty equivalent.

In reality, things vary because of the technology in use (in print, subtractive colour invariably adds black ink, in order to achieve solid blacks). Colour film is a strange beast, its behaviour controlled by the achievable chemistry. When the developer works on the exposed silver halide in film, the results react with other chemicals to create clouds of dye. Making that work three times to create three primaries and a colour image was nothing short of miraculous, and results are affected by the compromises involved. Also, photochemical film has very nonlinear brightness response, meaning that colours are rendered differently in highlights and shadows, with generally less saturated highlights. These are not specifically related to the differences between subtractive and additive colour modelling, but they are typical characteristics of film.

So, it's probably more accurate to say that film-style colour processing is emulating the foibles of film rather than that it's strictly getting much out of the knowledge that it's a subtractive system. There's also a brief mention of artificial intelligence with a diagram of something that looks a bit like a neural network. It would probably be possible to use a neural network on colour transform data, but no details are given on how it was done, or why.

But are these LUTs any good? It's entirely a matter of opinion. It's been said that Arri's 709 cube makes things a bit dark in the mid-tones, and The Brim's work certainly brightens things up and flattens them out. Possibly there's a creative intent to produce the low-contrast look of a cosmetics commercial. The company has claimed that these LUTs can't be reproduced using grading tools, which is possibly true in terms of the tiniest details but dubious in general; there's not much Resolve absolutely can't achieve. Juan Melara put up a video in which he claims to reproduce the look by hand. It’s not absolutely perfect, but like many things, it's probably close enough.

Tags: Post & VFX

Comments