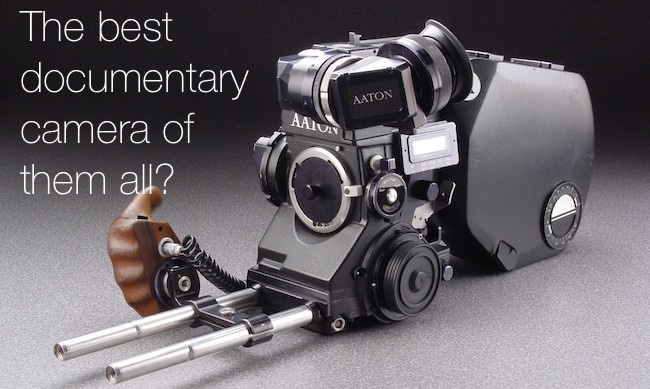

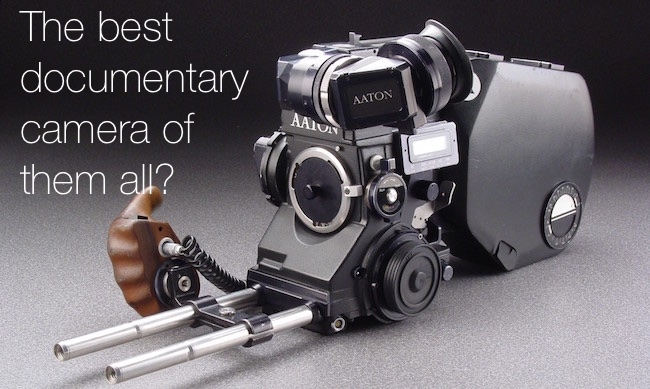

The Aaton XTR PROD - still available to hire

The Aaton XTR PROD - still available to hire

Roland Denning on where it’s all gone wrong for the modern documentary camera and some suggestions on how to put its evolution back on track.

It may be a controversial view on this site, but image quality is not necessarily the most important aspect of a camera when it comes to documentary use. Let me elaborate on that: modern digital cameras can produce fantastic pictures, but what distinguishes great documentaries is seldom to do with picture quality, it’s to do with what you are actually able to record. Of course, we aim for the best quality images we can get, but there’s a lot more to a camera than getting the most beautiful pictures. And from this perspective, frankly, the evolution of the documentary camera has gone astray.

I started working in documentaries in the era of film when quality of image was largely dependent on lenses and filmstocks. This meant camera manufacturers competed on making cameras lighter, quieter and ergonomically refined. From the almost-impossible-to-handhold ARRI BL through the Eclair NPR and CP16 to the ARRISR and Aaton, 16mm cameras evolved radically from the 1960s onwards to meet the demands of documentary filmmakers.

And here’s the crucial thing - the development of the lightweight 16mm camera, crystal sync sound, fast zooms and fast filmstocks was not so much about getting better quality pictures as making films that previously just couldn’t be made. For the pioneering cinema verité filmmakers of the 1960s, this meant you could put a camera in a rucksack, jump on a plane and go shoot a film - this simply hadn’t been possible before. A parallel breakthrough occurred almost four decades later with the advent of the DV camera which created a whole genre of low-budget personal documentary and more recently with the advent of the GoPro. But there have been steps backwards too.

The unfortunate rise of the DSLR

The irresistible rise of the DLSR has changed the way films are made and not necessarily in a good way, particularly for young filmmakers who seize on DSLRs as their way into the business. DSLRs can create beautiful pictures for very little money but have real limitations as documentary cameras. In fact, the move to DSLRs has imposed its own particular constraints on documentary form; shallow depth of field is great for interviews but if you are following real life around spontaneously shallow depth of field is a menace (I have seen far too many TV docs where only the tip of the nose is in focus).

There is an undeniable visual appeal in shallow depth of field - it evokes cinema, of course - but it also aestheticises and separates; in a documentary you generally want to see as much as if going on in the frame as possible, to allow the viewers to observe and make their own connections (there are some political implications here which I won’t go into now). In 1940s cinema, large depth of field was called ‘deep focus’ and hailed as a breakthrough for these very reasons. Since DSLR cameras were never designed to shoot movies, a whole industry has developed creating complex and generally clumsy rigs. Getting decent sound usually involves a separate recorder — not necessarily the end of the world, but a retrograde step in video terms. And not being able go from a wide to a tight shot without changing lenses is a huge restriction. This has evolved a particular style of documentary photography - more studied and set-up, a camera that does not move much (and if it does, it is probably sideways on a slider). Rather than capturing, spontaneously, events as they happen there is a tendency to set events up for the camera.

There are great documentaries made in this way — think of the work of Errol Morris — but for the observational documentary the technology is inappropriate (and also for certain styles of improvised drama, a movie form now almost lost). When technology is determining how we make films rather than the other way round, something has gone wrong.

The Aaton XTR was, to my mind, the peak of 16mm camera evolution; a camera that balanced so well on the shoulder it felt part of you and the hand-carved walnut handgrip that was cool in the summer and warm in the winter was some sort of immaculate conception. I should emphasise here despite my love of film technology and the discipline around it (and I’ve owned both an Aaton XTR and an ARRI SR), I am in no way nostalgic for the days of film; the advantages of modern digital technology, certainly for documentary work, far outweigh the benefits, real or imagined, of film.

The problem, as I see it, is that video cameras have evolved along trajectories that don’t seem to really coincide with the needs of documentary filmmakers. The ergonomics of the shoulder-mounted broadcast video camera have changed little since the introduction of Betacam 30 years ago. Other professional video cameras have evolved from stills cameras (or often, in fact, are stills cameras) or are developments of domestic video cameras. And some seem to have been developed for an alien species like the Black Magic Cinema Camera, impressive in so many ways, but exactly what sort of human being is it designed to fit? In this respect, camera design seems to have regressed 50 years.

There are of course, some great digital cameras available today. The ARRI Amira is a beautiful camera which can create fantastic images, and it is designed to sit on the shoulder, but the large sensor means you can’t have a lightweight, fast long zoom lens and the sort of depth of field needed for documentary (Yes, I know you can put on a B4 adapter on the Amira but this is i) clumsy ii) you lose a lot of light). It’s also bigger and heavier than I want a modern documentary camera to be. And of course it’s expensive.

At the other end of the scale, take a look at the new Sony PXWX70: compact, cheap, 1in chip, upgradeable to 4K - what could be wrong? Well, the zoom ring is also the focus ring (there’s a switch on the side to control the function) and iris is controlled by a thumb wheel. For me, that’s absurd, an ergonomic deal-breaker. It feels like a camera that has built on a merger of broadcast and domestic camera technologies rather than being designed for a specific purpose.

The modern documentary camera wishlist

So what might an ideal documentary digital camera be like? The following thoughts are, of course, full of my own personal prejudices and may well be peppered with ignorance. I’m sure there’s many waiting in the wings to tell me my ‘perfect camera’ more or less already exists or that my analysis is entirely unreasonable or erroneous. Anyway, here goes:

- I’d like a larger than 2/3” sensor, but small enough to enable a fast, lightweight zoom lens with a decent zoom range. Maybe just larger than Super 16 — say Micro 4/3 or even 1” — so it is still possible to let the background go soft on an interview, but enough depth of field to go wide and follow a moving subject around a room without it all being a fuzz. I want a zoom that goes really wide too. If that means two zoom lenses, so be it. It goes without saying I want low-light capabilities.

- I want the camera to be small and reasonably light, but more importantly I want balance, balance on the shoulder. I also want to be able to take it off the shoulder and easily use it with a flip-out viewfinder which can swivel round and accommodate every weird angle I want to hold the camera in.

- Direct control over focus and iris. Yes, automatic functions are often invaluable, but most of the time I want to pull stop and focus myself. Directly on the lens and not through some weird servo. I’m not interested in a follow-focus wheel unless I have a focus-puller.

- Now this might be a personal thing and seem very retro, but I’d really like a fluid-damped manual zoom lever. With a manual lever zoom you have immediate tactile and visual feedback on just where you are on the zoom range, and you can easily feather the end of the move. OK, I sense there are few takers other there for this.

- And this might seem even more retro and technically unfeasible, but I’d love a sharp, optical viewfinder that can show you well beyond the edges of the frame - so you can see what is about to happen before it enters the shot. Yes, I know, this is not going to happen either.

- I’d like four audio channels. My current Panasonic camera has four channels, but two of them are restricted to the entirely useless camera mic. I’d like to be able to run two radio mics on separate channels and a directional mono or stereo on-board mike.

- Focus assistance. Failing an optical viewfinder, I’d like a magnified focus assist that works in every recording mode.

- This is a minor thing but, I think, easily achievable:I’d like to switch between two white balances with a mix between the two states. If I’m going from indoors to outdoors I want the balance change to fade rather than cut abruptly.

- Storage - high-capacity, reliable, reasonably priced memory cards are now a reality. However, I would like to be able to back-up and transfer those files without having to lug a computer around with me.

- I haven’t mentioned codecs as that’s a whole other discussion, but it would be great to have the choice of recording directly to ProRes 422. The BlackMagic Pocket camera can do that, why can’t every camera do that now?

Am I asking too much or am I simply wrong? I’d be interested to hear your thoughts.

Tags: Production

Comments