Everything everywhere all at once. Kicking off a three part series looking at the evolution of documentary filmmaking, Roland Denning charts the technology that took us up to the early days of digital video.

Since the Lumière Brothers at the end of the 19th century pointed a camera at workers leaving the factory or a train coming into the station, there have been filmmakers whose main desire has been to record the world as it is, as it happens.

Lumière Brothers – workers leaving a factory

But technology stood in the way. Cameras were too big and heavy or too noisy, they needed too much light, recording synchronous sound was problematic, film stock was expensive. Now, none of that is a problem.

We all have phones that can record video and audio, and when we are not recording each other, surveillance and body-worn cameras record everything else. In television, fixed-rig and action cameras can cover every angle. Now we can record everything, everywhere as it happens, what is the role of observational documentary?

Recording everything everywhere – the Axon body-worn camera

Filming everything everywhere as it happens

Throughout history there have been filmmakers rebelling against the fantasy world of the movies to present the ‘real’ world that we are living in – the British documentary movement of the 30s, the cinema verité of the 60s, direct cinema, observational documentary, reality TV… For many of these movements, the implication was that if you film the world with the minimum of intervention, without narration or effects or formal interviews, you can capture a truth.

But just placing a camera into a situation begins to construct a narrative. Although people soon get used to the presence of a camera, making someone the subject of a film starts a process of storytelling. And, unlike the movies, life does not come in stories.

TV news – somebody telling you what you have missed

Many of the technical innovations for observational documentary were developed for television news. If you ever work in TV news, you soon realise that your job is generally to turn up after something has happened to film someone telling you what you have missed. The majority of news reports are a response to a press release, or a record of a pre-planned announcement or event. Just look at this 1950s advert for the Auricon camera; it is a man telling you about the capabilities of the camera.

State-of-the-art sound film recording in the 1950s

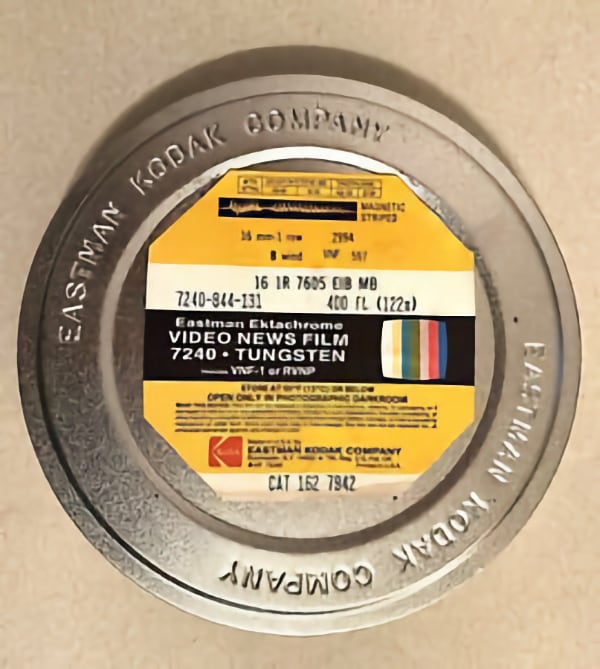

Let’s look at the technology. The Auricon pioneered portable sync audio in the 1950s by recording on the side of the film itself (initially optically, later magnetically) on reversal stock. The disadvantages were obvious: you could only record sound when the film was running, and because the sound head was several frames after the gate, you had to lift the sound off the film to edit. Also, reversal only had a latitude of about half a stop and the fast stock was horribly grainy. Nevertheless, single-system sound (commag) was in common use for TV news into the late 1980s, the Auricon often replaced by a CP16 or an Arriflex BL fitted with audio heads.

Reversal film with magnetic stripe – the standard for news film for many years

By the mid 1960s, American documentary makers like Leacock, Pennebaker and the Maysles brothers demanded a kit that would fit into a rucksack so they could jump on a bus or a plane and shoot anything. Anything more sophisticated than news needed a separate recorder, and sync was achieved by running a cable to the recorder (usually a Nagra) to record a sync pulse generated by the camera. They developed a way controlling (rather than recording) the camera speed with a pulse from a Bulova Accutron watch (actually a tiny tuning fork) to dispense with the sync cable.

In the 70s, crystal sync control, using a quartz crystal to provide the pulse, would become standard. One crystal would control the camera motor, and another record a pulse on the ¼” audio tape (because tape has no sprockets and can slip, it is not feasible to control the tape speed accurately). In the 80s, timecode simplified sync sound further.

Trailer for the Maysles’ 1970 Gimme Shelter featuring the Rolling Stones. Cinema verité at its peak.

Miserly film use

Even though by the 1980s the tools were relatively light and portable, you could go almost anywhere and shoot spontaneously, there were still constraints – film was expensive.

In the early days of my career, shooting 16mm for TV news and documentaries, it was not uncommon for a director to start an interview only on sound and cue the camera to turnover only when the interviewee was saying something interesting – and then turn the camera off again when it got dull (film cameras turn on and off instantly). I suspect many editors wished we worked that way today.

I worked with companies that would bring with them just 2 rolls of filmstock - 20 minutes worth – for a whole day’s shoot. And go back home with a short end (that’s the bit of unused film). The cost of film created a certain discipline, but it also made people think of sound and picture as very different creative elements – certainly a very positive thing for those learning the craft.

The author with his Aaton XTR – perhaps the perfect 16mm documentary camera

How video follows the film form

16mm retained its position as the primary documentary format until Betacam arrived in the 1980s. It wasn’t the first broadcast-standard portable video format (that would have been BVU U-matic), but it was the first to be seem as a viable replacement for 16mm.

Like 16mm cameras, but unlike the video systems that had preceded it, the camera and recorder were a one-piece unit. The cameras were also designed from the start, like later 16mm cameras, to sit on the shoulder – which of course, at the time, was taken for granted.

As was a parfocal zoom lens with at least a 10 to 1 ratio. In a retrograde step, the camera recorded audio and the sound recordist was once again tethered to the camera by an umbilical cable.

Professional video cameras, whether analogue or digital, continued to follow this form – a one piece, shoulder-mounted camera with a long range zoom lens – unquestioned until well into the 21st century. Today, that might be seen as a niche form factor – the ENG camera - but for several decades it was a standard form of equipment that brought with it a certain style of filmmaking. Yet today, a basic iPhone can produce better pictures than the most sophisticated 20th century documentary camera.

What interests me is not just how technology evolves to fulfil the needs of filmmakers but how the technology itself determines the way we make films. Now the ability to film everything all at once is commonplace, what is left for the documentary director? And are we still stuck with techniques that are a throwback to the last century? I shall address these questions in the next part.

Tags: Production Documentary

Comments