Replay: The battlefields of the audio visual world are littered with the corpses of dead formats, none more so than the fight to put moving images on to discs.

The first notable success was the LaserDisc, developed by Philips and Pioneer at the end of the seventies, which used laser technology (similar to that used for CDs) to playback analogue video and audio. RCA had a competing cheaper but unsuccessful product, SelectaVision, that used a stylus rather than a laser. Following the success of the audio CD, launched by in Philips and Sony 1980, Philips introduced CDVideo (digital audio with 5 to 10 minutes of analogue video), confusingly later replacing it with the all-digital VideoCD in 93. Philips also introduced the unsuccessful interactive CD-i in 1990, probably the first disc format to offer full screen digital video. To add to the mix, Commodore had their own soon-to-fail format, CDTV, in 1991.

With the exception of LaserDisc, none of these formats took off worldwide (although VideoCD did remain popular in Asia). But these are not the focus of this story. My subject here is a curious format that which, although it became well established, fell far short of its ambition. And that is the interactive CD-ROM.

Unlike the above attempts to put pictures onto disc, which all featured some sort of dedicated consumer device, the CD-ROM ran on your computer. This immediately solved the problem of how to get people to buy players, since this was the time when home computer sales were booming, but it presented another problem: what were these discs actually for?

Pre-internet information interactivity

CD-ROM came into the world in the early 90s, just before the internet had really taken off (and if you had access then to the internet it was through a slow dial-up modem, which meant the line to the internet was often engaged and you were greeted with a busy tone).

The emerging CD-ROM industry saw itself as separate from the fledgling computer games industry (still working mostly on floppy disc) and very different from the movie business. This was something new and exciting – a format with pictures and sound you could interact with. It couldn’t deliver full screen, full motion video, but it could give you decent audio and lovely graphics with lots of things to click on to lead you to other screens. The exciting thing about CD-ROM was it was interactive – but what did that actually mean?

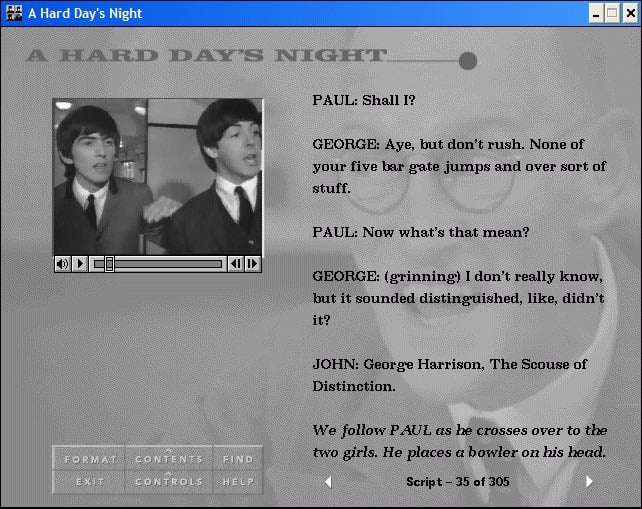

Interacting with A Hard Day's Night CD-ROM. Video playback was at 12fps.

No one was quite sure, but education featured prominently in the early releases. Many followed the form of a visual encyclopaedia, or the pages of an illustrated book. There were some interesting art projects and forays into softcore pornography, but the overall attitude was that the CD-ROM was some sort of learning device.

I briefly worked on a pilot project for a book publisher (never realised) to teach film making via a CD-ROM; we got as far as a 3 point lighting set-up you could reveal in stages. I also shot interviews for discs that were given away on the covers of computer magazines.

Compatibility

CD-ROM seemed to be particularly popular on Apple Macs. Macs were still (just about) in ascendance, and HyperCard (a basic programming tool supplied free with Macs) made it relatively easy to author a disc. Mac discs were, of course, not PC compatible and PC discs would not play on Macs, although dual-format discs did emerge later. To make it worse, many discs had stringent graphic, disc speed and memory requirements (like needing at least 4MB of RAM!) which meant very often they just would not play.

There was a notion among some filmmakers that this was, somehow, the future of movies. I once worked for a TV production company that thought its library of programmes could easily be made ‘interactive’ and reissued to make loads of money. They, couldn’t, of course, and they didn’t.

The big problem with CD-ROM was that the technology could not deliver anything close to full screen movies. Even static graphic screens could be achingly slow to refresh. One of the much talked about CD-ROMs of this era was the 1964 Beatles movie A Hard Day’s Night, released by Voyager in 1993. The QuickTime movie ran in a postage stamp-sized screen at 12 fps, but this was partly compensated by the fact the screenplay ran alongside it. The disc also boasted ‘interactive menus for finding favourite songs and scenes, and special extras like an interview with the director and the theatrical trailer’. It retailed at the time for $40 – equivalent to around $70 today. A lot to pay for a 30 year old black and white movie running at half speed in a miniscule frame.

In the same year, however, one hugely successful release showed the way forward, and that was the HyperCard-based single-player adventure/puzzle game Myst, originally launched for the Mac in 1993. In six months it sold 200,000 copies, after porting to Windows it went on to sell well over 6 million.

Myst is one of the releases CD-ROM is now best known for.

Of course, out of the various notions of what CD-ROM was for, games would end up being the great winner, particularly after the rise of the dedicated games console. DVD arrived in the mid 90s to takeover as the premium format for movies, and most of the educational ambitions of the interactive CD-ROM would be subsumed by the internet. Stripped of its interactive aspirations, CD-ROM continued as way of delivering software and as a storage system. And the interactive movie, whatever that was, disappeared in the space between the games and the movie industries. You may well have the odd unplayable CD-ROM on your shelf, a curious reminder of an era full of unachieved ambitions and misconceived notions.

Tags: Technology

Comments