Review: The CineRangerFinder was clearly a very 'in demand' piece of kit judging by its crowdfunding success. Does the final product measure up? (See what we did there?!)

Of all the electronic assistance that's ever been available to focus pullers, the ultrasonic rangefinder is the only one that's ever found wide adoption. It's the same sort of technology that helps cars warn drivers of an impending bollard when parking. To date, versions packaged for film and TV use have been horrifically expensive, anything up to eight or nine thousand pounds, depending on where you look, but crowdfunding may just have changed things a little.

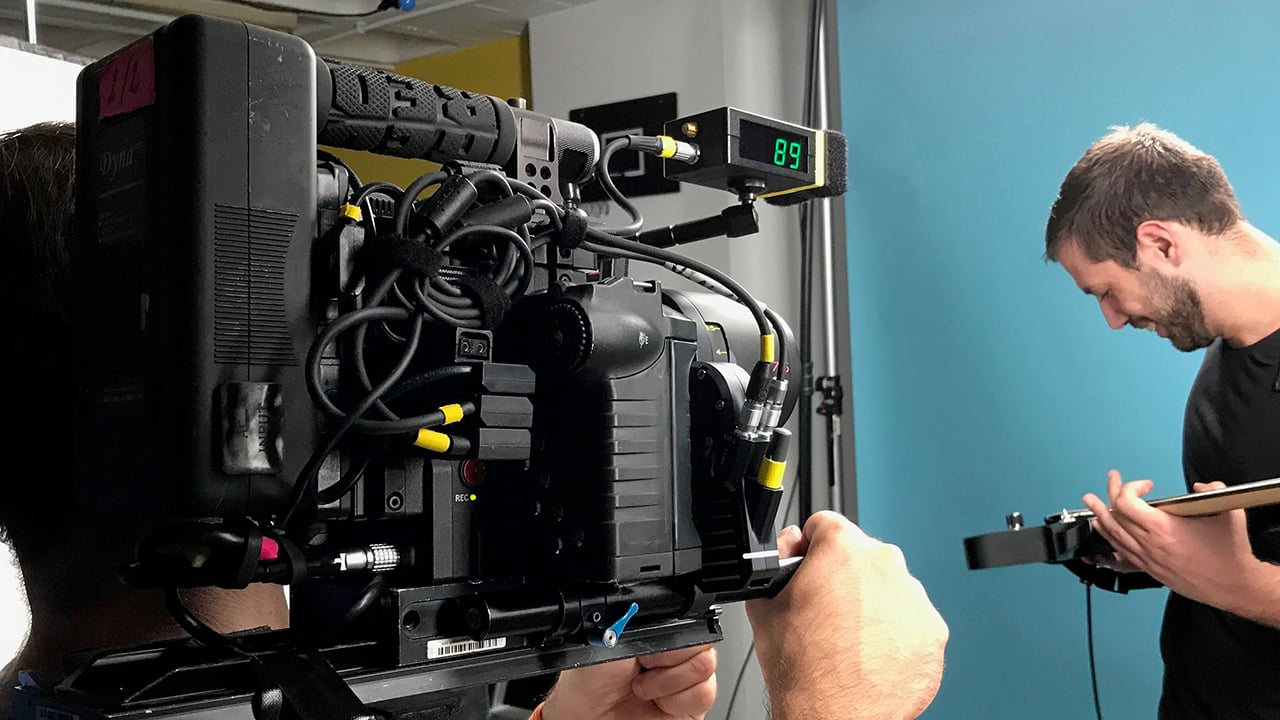

CineRangeFinder in use. Photo credit - Instagram @nicoflach

We don't usually cover crowdfunded products until they've successfully met their goals, but the CineRangeFinder project blew through its target on IndieGoGo on May 1st last year. It ended up achieving 143% of its £10,000 funding goal, so it's very much eligible for coverage, but it's also something of a vote of confidence in the technology. A reasonable number of people are apparently interested in ultrasonic focus measurement.

The business end. This is the ultrasonic transducer that does the distance measuring. A very, very faint clicking is audible at close range

Happily, the CineRangeFinder certainly doesn't feel crowdfunded, perhaps mainly because the excess funding made it possible to create a very tidy milled aluminium enclosure as opposed to the plastic or even 3D-printed cases which had originally been proposed. The two units on review here are the all-in-one sensor and display unit, and the remote display, for use when it isn't easy or possible to see the sensor. The fit and finish are very nice, forming tidy little blocks of metal that are powder coated in the slightly textured satin black common to camera gear. There are three buttons on both the standalone device and the remote – they both mirror the same functions – which are recessed fractionally below the level of the outer shell and feature a nice positive click.

The power connectors appear to be imitations of Lemo's products, but they're a widely used type and are, crucially, latching. A D-tap power cable is provided for each device. About the only oversight in the mechanical construction is that the 1/4” mounting threads are tapped directly into the aluminium body of the case. Really they should have steel thread inserts, especially given that this is a fairly coarse thread that's likely to be wound in and out reasonably frequently as cameras are reconfigured. OK, it's unimaginably better than the 3D printed case would have been, but with any luck, they'll be able to make this change at some point.

Radio frequency

A rationale is given on the website as to why the 2.4GHz radio band was chosen for the sensor-to-display communications. 2.4GHz is a crowded band, with lots of consumer devices using it and even more on film sets. However, it's generally unlicensed worldwide (with some caveats) and it's a lower frequency than the more recent, less crowded 5GHz area. Lower frequency signals tend to have better behaviour in buildings, although usually, the camera won't be all that far from the focus puller. Rules on 2.4Ghz devices vary slightly worldwide but in general, the radio link seems reliable.

In use, the rangefinder behaves much as any other device of its type. We're told that the detection cone is something like a 24mm lens and that feels reasonable in practice. That sort of fairly wide cone can create a situation where the indication is a much shorter distance than it instinctively should be, but it then becomes obvious that some nearby object is intruding on the edge of the detection area and provoking the closer reading. Some rangefinders offer clip-on tubes to narrow the detection radius and there is talk of this sort of accessory for a future version.

The sensor-display module can be used alone, or with an accessory remote readout

Outside of that, CineRangeFinder does what it aims to do in terms of the core measurement features. There are a few extras it could have, particularly synchronisation, to prevent the ultrasonic signals from one rangefinder from interfering with another, but that won't be a dealbreaker for most people. Rangefinders in general work very well for situations such as very slow dolly or crane push-ins or any situation where it's easy to wander gradually out of focus; it's not an autofocus and it will always rely on the focus puller's interpretation, but it can help a lot with precision.

With the very nicely made metal enclosures, the rangefinder won't look out of place on even the highest end camera outfit. It looks expensive, but is it? Well, the currently available version of CineRangeFinder sells for £450 for the all-in-one device, with the ultrasonic emitter on the front and displays on both sides. The remote display and control unit costs another £250, and there's a £550 combo deal representing a £100 saving. That's still not pocket money for a device that does exactly one job on exactly one kind of shoot, but it's so much less than the incumbent product that it's likely to attract attention.

This means two feet, one inch. Metric readouts are also available

Crowdfunding can be great, in that it can provide pre-sales for niche products which means that those niche products get to exist. In this case, it ensures that people who really need a rangefinder can have one much more easily than ever before, and a very credible one at that.

Tags: Production

Comments