We're republishing this article because of the recent news that Jim Jannard, founder of RED cameras, is retiring. Many people (including me) claim that RED is responsible for the modern digital cinema industry in a way that no other company can claim to be, and what it boils down to is that the Irvine-based camera company was the first to break away from "broadcast" video standards. HereI talk to Graeme Nattress from RED about the epic journey the company has made, and the complexities of designing a revolutionary video camera.

Introduction

Digital video has reached the stage where the "film look" is relegated to a subset of the capabilities of a digital camera. The basic tenets of digital cinema cameras - for example: that you have a single sensor with a Bayer-pattern filter - are widely accepted.

HDR and wider colour gamuts are here. At the same time, resolution has increased to the point where currently available cameras - sporting 8K sensors - have around 80 times more pixels than digital cameras from the era of standard definition.

Luckily infrastructure - that's bandwidth, processing and storage - has kept pace with this rate of change.

Moore's law has largely taken care of these increased demands. But what the famous (and now almost exhausted) empirical rule can't do is make largely subjective aesthetic changes. For that you need humans, preferably with good eyes and definitely with a feel for creative mathematics.

RED's Graeme Nattress fits this description perfectly: he's articulate; a great communicator, and just “gets” that not always obvious relationship between the real world and the technology that’s designed to capture and reproduce it.

Graeme lives near Toronto, Canada, and I flew there to spend two days with him, discussing the biggest issues in modern camera performance, not to mention, philosophy, electronic music and vintage HiFi systems.

Graeme has been at the centre of the digital cinema camera revolution. RED was the first company to announce a practical cinematography camera with 4K photosites at a time - 2006 - when HD was still being rolled out by broadcasters. (RED Camera design and engineering started end of 2005. RED ONE was announced at NAB 2006.)

I wanted to talk to Graeme because he's been involved in digital camera imaging from the start of RED and it's rare to get the opportunity to talk to engineers working at the cutting edge of cinema camera development. But this is exactly what Graeme is doing.

The following articles are based on my conversation with him.

The journey from standard definition video cameras to 8K cinema shooters has been anything but inevitable. Instead, it’s been a bumpy ride, where some of the biggest undulations in the road have been caused by the laws of physics, which resolutely refuse to give way, however much we might want them to.

This has been the reality, and it’s by accepting this and tackling it in a realistic and “adult” way, that the biggest progress has been made. We will see in this series that, often, sensible compromise is the straightest route to genuine progress and outstanding performance.

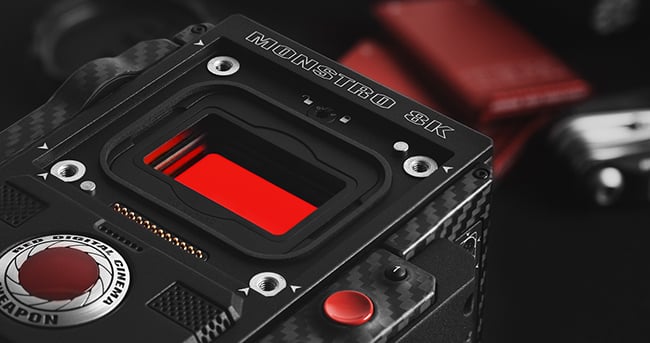

WEAPON with MONSTRO 8K VV

For a taster of what’s to come, here’s what Graeme Nattress said about the very early days of RED:

“At that time, the biggest thing holding everything back was ‘broadcast standards.’ With analogue it was obvious that everything had to tie into the same standard or it would never work. With the introduction of digital non-linear editing we saw that wall start to crack. The mess over the HD standards (a mix of 720p and 1080i, different sizes and frame rates and interlace, along with the historical mess that is non-integer frame rates and the associated drop-frame time-code) didn’t help.

Once video was computer data, moving images could be any size and any frame rate within the power of that computer system. Just as film was not tied to a distribution format (so was output agnostic, and could easily be made to work with any TV broadcast standard around the world), computer based video didn’t need to be tied to a particular standard either.

At the point of RED ONE launch (or even before), it therefore made sense to make the image acquisition the best possible without regard or limit to broadcast standards.”

We’ll look at the issues around designing a cinematic digital video camera and how often one problem can be masked by another one - solve one issue and another one pops up in its place, possibly less serious, but still defiantly in the way of a “perfect” picture.

We’ll also see how some perceived problems - like the loss in resolution caused by the Bayer Filter Pattern necessary to extract colour from a single sensor - are actually masked by other factors like Optical Low Pass Filters (OLPFs).

And we’ll see how as resolution increases, the significance of many issues that were big in lower resolutions, diminishes as the number of meaningful pixels in a picture increases.

WEAPON with MONSTRO 8K VV

We’ll talk about noise: how sometimes it’s good, and sometimes it’s bad, and how there are different types of noise, with different origins. And we’ll look at how a wider neutral colour space allows for better images from the sensor, and more freedom in post.

There’s the concept of micro-contrast and macro-contrast: Sensor MTF vs Lens MTF.

And finally we look at how sometimes mathematics suggests a way to improve a picture, but that people in the real world - as opposed to theoretical - disagree. It’s taking the right approach to these awkward situations that leads to the best pictures for the biggest number of people.

Watch out for the first part of the interview with Graeme Nattress, coming soon.

Tags: Production

Comments