Replay: Mention the word "autofocus" to a traditionalist and you might risk being burnt at the stake. However autofocus today is incredibly effective and accurate, so why is not not being adopted more into higher end camera systems?

The film and TV industry has always been very good at resisting the intrusion of upstart technologies. Put another way, it’s a Luddite behemoth terrified of change that clung to 35mm film for about ten years longer than it needed to, just because it was cool. At the same time, though, we seem to be sleepwalking towards a few other changes.

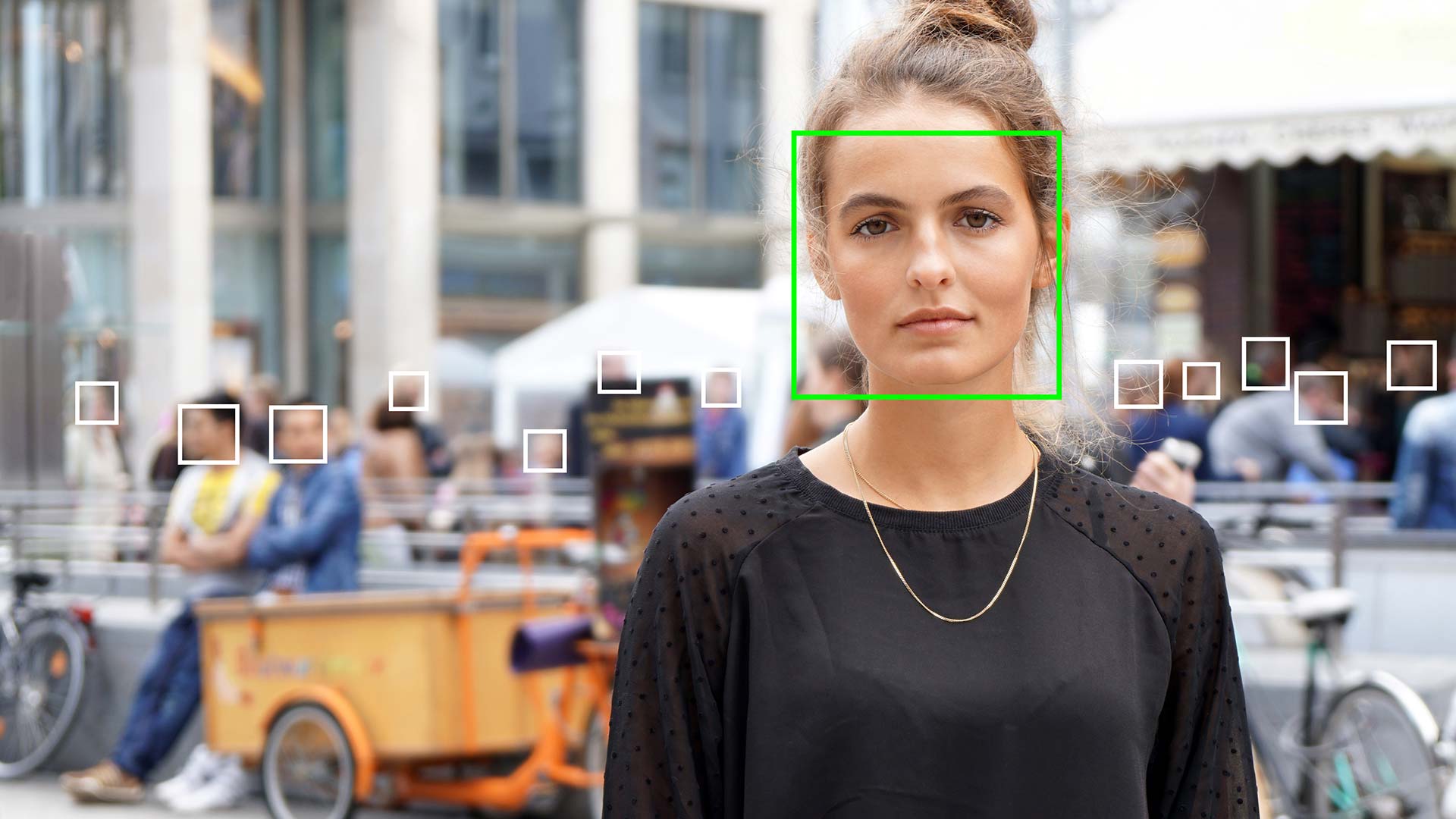

Chief among those changes is a now confidently predictable alteration to how lenses work. “Autofocus” was rescued from ignominy through the efforts of organisations like Canon, which has demonstrated performance that would be practically supernatural from a human focus puller. The problem is that the sort of lenses generally preferred by single-camera drama crews are not the ones that have the type of electromechanical systems that autofocus systems like Canon’s demand.

Or, to put it another way, at some point, someone’s going to realise that there’s no such thing as a 300mm Cooke S7 that can hold an approaching motorcycle in focus in the same way a massively less expensive stills lens can. Of course, a proportion of the audience will be choking on its real ale at that comparison. Still, there’s an uncomfortable reality here: expensive high-end lenses can’t currently do something impressive and at least sometimes useful, such as autofocus, that much less costly options sometimes can.

The Canon XF705, a camcorder with excellent autofocus. Image: Simon Wyndham.

Do we want autofocus?

If we decided we wanted these high-end autofocus systems on high-end cinema cameras using high-end lenses, that would mean standardised control systems, and standardisation is difficult. It required a genuinely Herculean effort from Cooke, over several attempts, to get anyone to use a lens data system. Even then, there are now two mutually incompatible and competing versions from different manufacturers. Giving high-end cinema cameras sufficient control of lenses that they could use internally-generated focus data would require scaling a similarly-sized standardisation ziggurat, and engineering a meeting of the minds between focus motor and camera technologists.

That could be done, at least technically, if not politically. It’s not clear, though, that the techniques used in stills cameras autofocus systems can even be made to work using movie primes and focus motors. Stills camera autofocus doesn’t work the same way as a focus puller. Someone wielding a remote focus controller estimates the required focus distance and sets it. Modern autofocus works very differently, detecting whether the target is closer or further away than the current focus distance and adjusting to compensate. Your DSLR doesn’t read out the focus distance because it doesn’t know it; it doesn’t need to know it.

In one way, that helps; there’s no precision calibration of the lens required, assuming it can adjust the focus reasonably quickly and in small steps (that’s why amazingly effective autofocus even exists on affordable stills lenses). The only command to the lens needs to be “further” or “closer”. Improved performance comes from such innovative commands as “further a lot” or “closer slowly,” but the principle is straightforward. The problem is that this technique is heavily reliant on fast feedback, and a focus motor on a movie lens does not have the sort of snap and immediacy of a good stills lens. This is because the parts are larger and heavier – it’s fashionable for them to be large and heavy. Some of the electromechanical approaches common in stills lenses really don’t work very well on bigger, heavier designs.

The Sony A7SIII. Also extremely good autofocus.

Fundamental lens redesign

As such, to make high-performance autofocus a reality, we might be looking at a much more fundamental redesign of moving-image lenses to use the same sort of electromechanics and the same techniques of the overall build as stills lenses. Given the harsh working environments tolerated by the best stills equipment out there, there might not be any significant problems with ruggedness or solidity, but operability is another matter. Stills lenses of that sort don’t generally offer a particularly wonderful manual focus experience. What we’re talking about here is potentially something like the Canon CN-E 18-80mm T/4.4. Anyone who has used it will be aware that it does sacrifice some of the manual operability of the fully mechanical ENG lenses that it (to some extent) replaces – and it’s at its best, by far, on Canon cameras.

In the end, this is a chicken-and-egg situation. First, both the AF system in the camera and the controllable lenses are required simultaneously, meaning someone has to make the leap. And then someone actually has to work out how to create the autofocus system in the camera, in a situation where the sensor work is usually performed out of house. Canon, remember, makes not only the lenses and the bodies but also the sensors in its own plant. So what other company has very competent AF in its cameras?

Sony. Which, no surprise, also makes lenses, bodies and sensors in house, or at least under a very closely controlled contract. Although thinking about it, Arri does too, and some of its cameras can already run lens control motors. It makes you think, although Arri’s dedication to the traditional approach might make it anxious to avoid bruising the egos of the world’s focus pullers, regardless of the broader implications.

Conclusions

Either way, there are a few barriers to making the sort of highly-competent AF we see on certain specific combinations of equipment available on arbitrary gear. Nevertheless, it seems like a stretch to assume that those barriers will remain uncrossed by an industry that spends so much effort looking for new features to add to increasingly mature product lines. Possibly it’ll be something we’ll see first on more affordable cameras, the sort of thing often seen on shows where top-gun distance-guessers are rare.

At the high-end extremes, it seems likely that people boasting twenty years’ experience twiddling a dial will want to go on twiddling, and discerning directors are likely to be very happy for them to do that. In the long term, then, we’re likely to want to retain the ability to do that while simultaneously being able to resort to a highly-developed AF system at our option. Manufacturers take heart, then: demanding the best of all worlds, all at once, is what keeps things reassuringly expensive.

Tags: Technology Production Cameras

Comments