Replay: When it comes to seemingly infinitely increasing resolutions it is all too easy to forget that there are very real, and much needed, reasons why they are required. And it goes well beyond conventional video and filmmaking.

Moviegoers are satisfied

When we talk about technologies at the extremes of the media industry, it's often in the knowledge that we aren't really talking about conventional film and TV. Resolutions much beyond 4K are possibly, maybe, one of those things – at least in terms of distributing them to the home, though the big manufacturers seem keen for things to be otherwise. Movies and TV shows as we've known them seem likely to continue more or less as they are. People like the unreality of comparatively low frame rate, for instance, and more resolution doesn't add materially to the value of the production. Radio conveys more of the speaker's intent than printed words, but radio didn't kill off books. TV gives us even more, but it didn't kill off radio. People like reading and radio on their own merits. People like the current approach to movies and TV shows on their own merits.

As Sony has put it in the past, resolution for conventional film and TV work is largely a won war

But fear not, people with gear to shift. There are a few places where the picture quality war is still very far from won. They're not conventional film and TV, but one of them is VR, which demands huge amounts of resolution so that the display can adequately fill the viewer's complete field of view. When Oculus originally produced the first development kit, DK1, in 2012, it used a 1280 x 800 pixels display. That display was effective in demonstrating the basic idea but was quickly identified as pretty inadequate, because it made everything look like it was being viewed through a black grid. It was more or less the first target for improvement and the company showed an improved prototype with a 1080p display in 2013, though that model was never made publicly available.

Sony-based multi-camera array for 360-degree video.

The second development kit, DK2, offered more of everything. It recognised the need for high frame rate, since a short delay between head movement and that motion being reflected in an updated image is key to minimising motion sickness. The original DK1 had been limited to 60Hz display updates, although Doom supremo John Carmack had intervened to recommend a doubling of the head-tracking update rate to 250Hz (and it was done.) The DK2 updates rotational information at 1000Hz, four times the DK1's rate, and increases display capability to 1920 by 1080 updated at 75Hz.

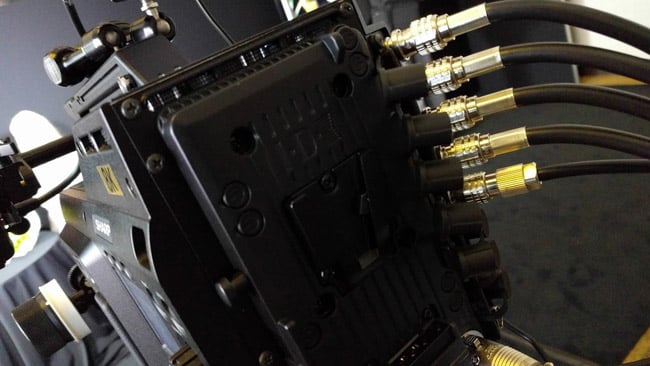

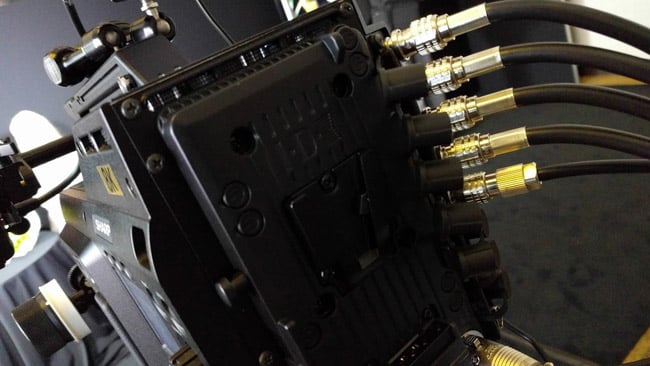

Possibly the first ever unified 8K camcorder. Wire standards for 8K are in their infancy, hence the multiple links

8K Ready

Users scream for more

As inadequate as the 800-pixel DK1 was, the much-improved DK2 was still viewed as not really enough and it's at this point that we start moving into the current cutting edge. Because, entirely unlike conventional film and TV distribution, VR users are still agitating for more pixels and more frame rate. VR is not about creating a sort of lyrical hyper-reality. It's about creating reality or, at least, a good enough reality that it doesn't make people feel motion sick and myopic. The problem is that, so far, VR headsets have leveraged cellphone technology just like anyone else with a need for a physically small, very high-resolution displays and they're starting to bump up against the edge of what's actually useful in smartphones which are not usually viewed from an effective distance of a couple of inches.

8K in the palm of your hand (then add the mattebox)

Oculus' latest Rift S uses a 2560 x 1440 display, the same resolution as a decent 27” desktop monitor. It's probably possible to go a fair way beyond this – the Sony Xperia Z5 was the first smartphone to use a 4K display and the company's XZ phone now offers both 4K and (some value of) HDR, which is probably at least as valid in VR as it is in any other display technology. Reaching into the future, HP has talked about a prototype headset codenamed Copper which offers 2160 pixel square images per eye, fractionally outdoing the total resolution of a hypothetical DCI 4K display. All of this needs to be considered alongside the field of view, since not all headsets fill the same amount of the user's visual field, and a smaller field of view will result in higher resolution for the same number of pixels. But that's to some degree a choice made when designing the optics.

More is here

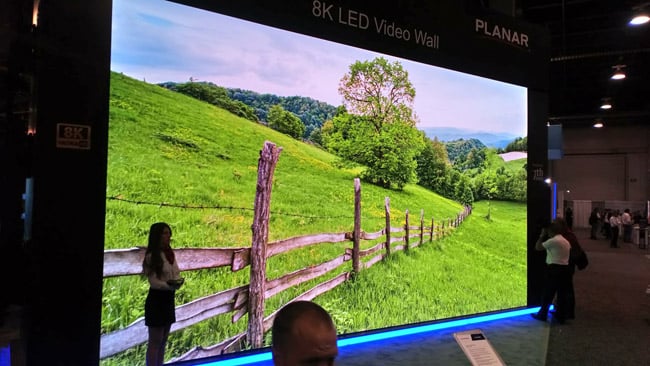

The person standing to the lower left of the huge LED video wall is normal sized

Going beyond the 4K level is apparently possible. Pimax and the Google/LG collaboration have both talked about systems capable of delivering around 4K per eye at competitive circa-80Hz frame rates. Does that make it an 8K VR headset? Well, yes, and if someone made a smartphone with a single 8K display, it might well be possible to stick it in a headset and make a VR tool out of it. Make that normal and suddenly we have affordable VR headsets based on tech people might already own, and a reason to make 8K smartphones into the bargain.

Possibly the first ever unified 8K camcorder. Wire standards for 8K are in their infancy, hence the multiple links

It certainly isn't conventional moviemaking, but it's hard to argue that it isn't a realistic application for huge pixel pipelines. Bring it on.

Tags: VR & AR

Comments