Live television broadcasting is a high pressure environment on the best of days. But it puts a whole new perspective on things when you read this account of working in the BBC's VTR department back in the day. We've never had it so good! By Guest Author Simon Anthony

Even after my many years in TV operations, I can still find the job quite magical. The way you can chat with a person in the corridor one moment, hear them over the talkback the next, and then help millions of people see them on their screens at home is really remarkable.

From a very young age, I wanted to have such a job. My father already worked in the BBC Sound department and I wanted to join him there. My first attempt failed because I was too young. On the second try it worked but only for a post in the VTR department. I took it anyway, anything was better than my job of installing phones for the Post Office.

When I joined the wide world of television recording there was only one way that it could be done in the electrical domain. That was by means of a Quadruplex VTR. This machine came in various sizes from the 'Room' version to the large packing case variety. The latter was not all that good being a cheaper cut-down room type. Large blue room VTRs gave the best pictures, but for the shortest time as they damaged the tape and quickly degraded the pictures if the multiple settings were not lined up correctly by a fully trained engineer. I liked them, they gave beautiful results for hard work even before I was trained at all deeply.

The Ampex VR2000

The machine that fully captured my love and devotion was made by Ampex, the VR2000. This was also large but not a total room of a machine. Predominantly grey originally, it was full of valves and only worked in black and white, but it was so well designed mechanically, over-designed by today’s standards, that it was capable of being upgraded to work in full 625 line colour. As the machine was American, it was basically of a 525 line standard. When first used in this country, long before I ever got my hands on one, it ran in the old 'High Definition' 405 monochrome standard that was used to record such all-time greats as the entire lives of the first two Doctor Who's. The tapes used were at first very expensive – even today it costs a pound a minute for full broadcast quality (That is soon to change but not for the best yet, more of that later.)

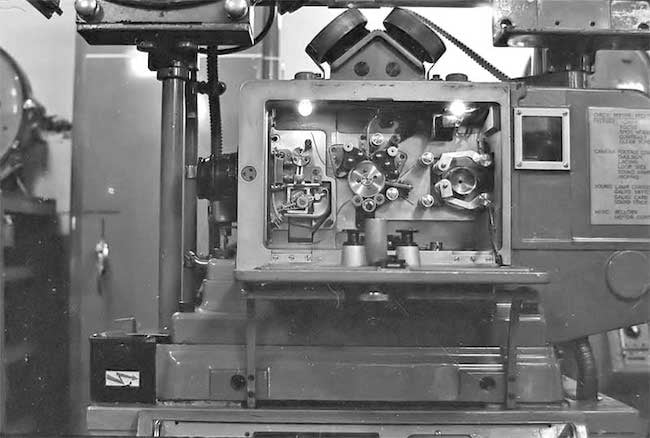

The Ampex VR 2000B - Image courtesy of Chris Booth at BBC VT - A record

These tapes were very bulky being two inches wide running for one and a half hours at 15.625 inches per second. The spools were so big that it took a very big or stupid man to carry four of them at once in the protective boxes. The size of the tape did not change with the television standard as that too had a lot of spare improvement space in its design. The result of this was that storage of the tapes was very costly, so they were wiped and re-used as often as possible. For the early tapes, this meant two trips before being junked or put into vast libraries to be lost and forgotten about. Hopefully forgotten, because when the financial screws were first put on, the cost of storage looked like an easy cut. So vast numbers of programmes were lost forever, like the first two Doctor Who episodes.

Fortunately, recording on tape was not the only way of keeping electronic television programmes. Filming the telly worked quite well. The most remarkable machines were devised for this purpose. They used 35mm or 16mm film in a camera pointing at a special high-definition monitor manned by a senior engineer (who was normally deaf as the beast was a bit on the clanky side).

Filming television screens

The 35mm Telerecordings on FR cost more to run than the hearing of the operator, real money in fact. All of the programmes from the old 405 days that the BBC still has (almost) are films of the originals, often out of focus, set up by more and more bored engineers working in bad conditions. Is it any wonder the pictures now look so bad? A very few 405 VTR tapes still exist. They and the few full-price 35mm FRs show how very good the definition was in those days, better than it often is now! Honest! The Good Doctor. only lived on because it was sold to Africa and the Arabs who didn't have VTs but did have projectors. Still today the odd programme is flown home from there.

This machine was used in the early episodes of Doctor Who - Image courtesy of Chris Booth at BBC VT - A record

This hobby horse of mine can take me forever but I will leave more until later. To continue on the subject of the emotions at TV studios, people look very different when they know they are about to go on air. If you stumble on them accidentally, not as part of the shared job of making the programme, they look very human, very concerned and agitated. The makeup somehow hangs on them, adding age and stress to faces that, when met as a colleague, are bright and confident. The flash of humanity, the gap in the teeth, the wart on the hand, the fact they really are rather short and dumpy, only comes through on the box when things go very wrong. I don't know how I change in times of danger such as those, but I can say what happens. First, I must say a little more about the machines used then.

The full 625

The old Quad VTs used a head that scanned the tape almost vertically taking in enough information to make up bands of 15 or 16 TV lines in each pass. It could only cover sufficient lines for the full 625 if the tape was moving, so there was never any picture when the thing was still. Because of the difficulty of getting the bands of lines to match each other timing-wise, the machines took a fair bit of time after pressing Play before the picture was fully 'locked up' and stable. So, no pictures in spool, either. These 20 bands could show up if the gain of any one of the heads was not matched to that of the others. This could also be seen if one head 'clogged' as four, equally spaced, horizontal bands across the screen. The only time the old Quad faults can be seen today is in the adverts. The ACR25’s ITV (one of the UKs main broadcasters) companies use, are over 20 years old and are still going strong.

Today, the heads on 'Helical Scan' VTs cover enough lines to make up one field of 312 or so lines which in the PAL system is good enough to make a full screen if each is shown twice. Such a Freeze is half as sharp, but as the next set of 312 might well show, detail that has moved in relation to the first lot showing all the proper 625 lines would also show a 'judder', so we don't. The home VHS and Betamax are helical scan and use the same sort of tricks. In 20 years none of these machines will work at all.

Rehearsals are where the mistakes are supposed to be made

Rehearsals are for making mistakes. The idea is you get it right next time. Some years ago now when working at BBC TV Centre in London running the trailers for coming programmes, I was not feeling too well. It was my first day back from nearly four months off with glandular fever. The idea was to 'snap me out of it' by going back and giving work a try. I was all right for the rehearsal, not the transmission. Tapes being 90 minutes long and trails lasting for only a few, each tape held lots. Every trail or programme has an identifying clock at the front (as seen on TV) but on the Quad nothing shows unless the tape is running. This time, the trail I had to transmit was different. It was a ten-minute long advert for the next day’s BBC Shakespeare Drama production – big money. It was different in another way as well - there were two clocks! — almost identical they were.

After showing the first few minutes of the programme at the rehearsal, I was told to reset on my ten-second cue for the transmission to network a quarter of an hour later. That waiting is horrible. I checked and double-checked that my cue was the right one. Knowing my brain was not fully up to it yet, I checked if even the most obvious mistakes hadn't been made; none of the traps tripped. Even then, maybe because of my attention, on air, things didn't go well.

I was waiting all right, ready and not trembling with my first transmission since going sick. The machine was run automatically then, but it was only a start pulse – it can't do anything about being in the wrong place. Things looked fine for those very first few minutes that had been rehearsed, then the 'Voice over' suddenly faltered and then stopped. In my mind, I could hear the production team of that recorded day think 'Never mind, take two on the clock, back to the top'. As those words went through my mind, the pictures ended as if having been pulled suddenly sideways leaving a trail of bits of the last line we had seen repeated 625 times down the screen. Then the machine coughed as it locked up on air, and after a bit, a perfect picture of a clock with 'take two ' written on it was seen by about five million people and it was all my fault!

To say I felt sick is not accurate. My mind was elsewhere as I watched the clock I was transmitting start to move. Then my pictures were mercifully replaced by an apology caption and the continuity announcer said something like: “We must apologise for the loss of that programme. Before the next programme, here is some music.”

By this time, my mind still not in the room with me, I had found the second clock cue and was ready to try once more, but it was too late. Worse was to come. The network supervisor decided to run the next programme early. Everything was now going to happen some eight minutes ahead of time because of me. My boss wandered into the room and asked if I was all right and what had happened. I was answering that question on the phone to the network controller as he came in, but I attempted to explain myself more than twice.

For some reason, perhaps the 'get-back-on-fast-after-falling off' hard school of horse riding theory, I was left to try again with the same tape after the early run programme had finished. We rehearsed once more. This wide tape can be written on with a white pencil type crayon, china-graph it is called. I had marked the tape that way. The tape counter reading was also written on the machine several times. Rehearsal worked, Take Two clock and everything. It was then my mind went back to bed. I reset on the wrong clock. My markings were also wrong as were the numbers, all wrong! Somehow when the standby signal was given, something told me it was all gone to pot. I ran the machine a few seconds late but from the right place. Then I went sick for another two weeks.

Header image: Shutterstock - Soundsnaps

For an even more nostalgic look at the role of a VT operator, check out this 'time encapsulated' BBC training video below!

Tags: Production

Comments