Replay: The ARRI 35 II was the camera that defined Kubrick and allowed a whole new wave of directors to create their visions with faster, creative shooting.

In the second part of this series, I looked at the classic Hollywood studio camera, the Mitchell BNC. Studios and crews loved the Mitchell – ways of working had grown up around it, it was a familiar and dependable camera - but there are always filmmakers pushing to make movies faster with smaller, lighter equipment, favouring location over the studio. In the second half of the 20th century, much of this impetus and the technology to achieve it came from Europe.

The major innovations in film cameras have been shared between the USA and Europe, and within Europe, Germany and France have been the key innovators. Within Germany, one company dominates: Arnold and Richter of Munich, better known as Arriflex.

Arnold and Richter built their first camera in 1924, but the first Arriflex reflex camera came in 1937, 30 years before a reflex viewfinder was an option on the Mitchell. It was the standard German newsreel camera in World War II and a treasured spoil of war when allied troops retrieved them from the battlefield. A US copy of the camera initially called the Cineflex and then the Cameraflex, was made in small numbers in the 1940s. After the war, Arnold and Richter quickly rebuilt their bombed-out factory and started exporting their cameras all over the world. Their first post-war camera was the Arri 35II.

Arnold and Richter built more than 17,000 Arri 35II cameras. Like the Mitchell and the Bolex, featured in the first two chapters of this series, this was a design originating in the 1930s that carried on to the end of the 20th century and beyond.

Arri 35II Mirror reflex viewfinder

The outstanding feature of the Arri 35II was its mirror reflex viewfinder system, superior to all other systems at the time. The mirror was on the spinning shutter of the camera, so when the shutter was closed as the film was being pulled down to the next frame, the image was redirected to the viewfinder. The reflex system allowed the operator to view exactly the focus and frame of the image in the camera gate without needing cumbersome rack-over systems or viewfinders attached to the lens. Unlike the pellicle reflex system on the 16mm Bolex, where a small portion of the light coming through the lens was ‘stolen’ and permanently redirected to the viewfinder, the operator would see a clear, bright but flickering image.

Gene Hackman taking over the camera while filming The French Connection - Attribution unknown

The 35II carried the film in 200’, 400’ or 500’ removable magazines. The mechanism of a movie camera is not that complicated. Firstly, it needs one or two sprocket wheels to drive the film steadily through the film chamber – in most Arriflex cameras, including the 35II, the sprockets are in the magazine rather than the camera, making threading the film through the camera and changing magazines faster. A claw – or claws – pulls the film down frame-by-frame in the gate and a register pin – or pins – holds the film steady in the gate. In addition, the take-up spool needs to be driven to wind up the exposed film. Some cameras forego the register pin and many amateur cameras, typically 8mm cameras, dispense with the sprocket wheels and register pins altogether, using the pressure of the gate to hold the film in place and the claw itself to pull the film through the camera.

No register pin

The Arri 35II lacked a register pin, but the mechanism was designed so the claw itself would stay steady and hold the frame in position for the duration of the exposure. Although, in principle, this meant it was not as steady as a Mitchell with its dedicated register pins, in practice, it was more than adequate for everything other than composite shots where two or more pictures would be superimposed over each other. The Arri35II could deliver great pictures.

Although I have attempted to tell these stories by picking a camera for each decade, camera evolution does not fit neatly into 10-year periods. Some cameras span six or more decades, others may reach their prime many years after they were first launched. Although the Arri 35II was first launched in 1941, by far the most famous and successful variant was the Arri 35IIC of 1964, with a greatly improved viewfinder, a camera that is still in use today. But I have other cameras to consider in the 1960s, so let’s give the 50s to the Arri 35II.

Handheld camera

The Arri 35II half-answered the dream of a small, portable cinema camera that you could handhold. I say half-answered because although the 35II was a lightweight camera that took great pictures, it was strictly what Americans call a MOS camera (‘without sound’): it made far too much noise for useable sync sound to be recorded. Arri released a blimp for the 35II in 1953, enabling it to be used for sync sound, but it made the camera much more cumbersome, adding 42lbs(19Kg) to the original weight of 13lb(5.8Kg), although that still made it substantially less than half of the 122lbs (55Kg) of the Mitchell BNC. Arri didn’t produce a self-blimped (inherently quiet) 35mm camera until 1972.

We can’t really consider the evolution of the movie camera without talking about sound. It was the coming of the talkies at the end of the 1920s that forced studio cameras to be heavy and cumbersome, and it was the increasing use of post-recorded sound that made cameras like the Arri 35II viable for feature production. Some countries, particularly Italy, have always favoured post-sync sound as it liberates the shooting process – not only does it make everything faster, but directors can talk or shout at actors while filming. The story goes that Fellini would get actors to merely recite numbers and actually write the dialogue after he had shot a scene. Post-recorded dialogue was also favoured in countries where it was common to produce multiple language versions of each production. Increasingly, filmmakers, however, longed for the realism of ‘original sound’ to accompany the flexibility of a lightweight camera, but they would have to wait until the 1970s to be able to do this in 35mm. An additional problem was that, until the 1960s when sync-pulse systems arrived, sync sound necessitated both the camera and sound recorder running off AC power which meant a generator truck if filming outside the studio.

The first recorded Hollywood use of the Arri 35 was with the 1947 Warner Brothers’ Bogart/Bacall movie, Dark Passage. The Arri, retrieved by the US government from Germany at the end of the war, was used for subjective ‘point of view’ sequences of the Bogart character.

Shoot fast

For much of its history, the Arri 35II was used as a second camera, often on location in places where a Mitchell just would not go, attached to cars or boats, used in confined spaces or hand-held, but from the late 1960s onwards, it was increasingly used as the primary camera as a new wave of directors wanted to shoot fast on location.

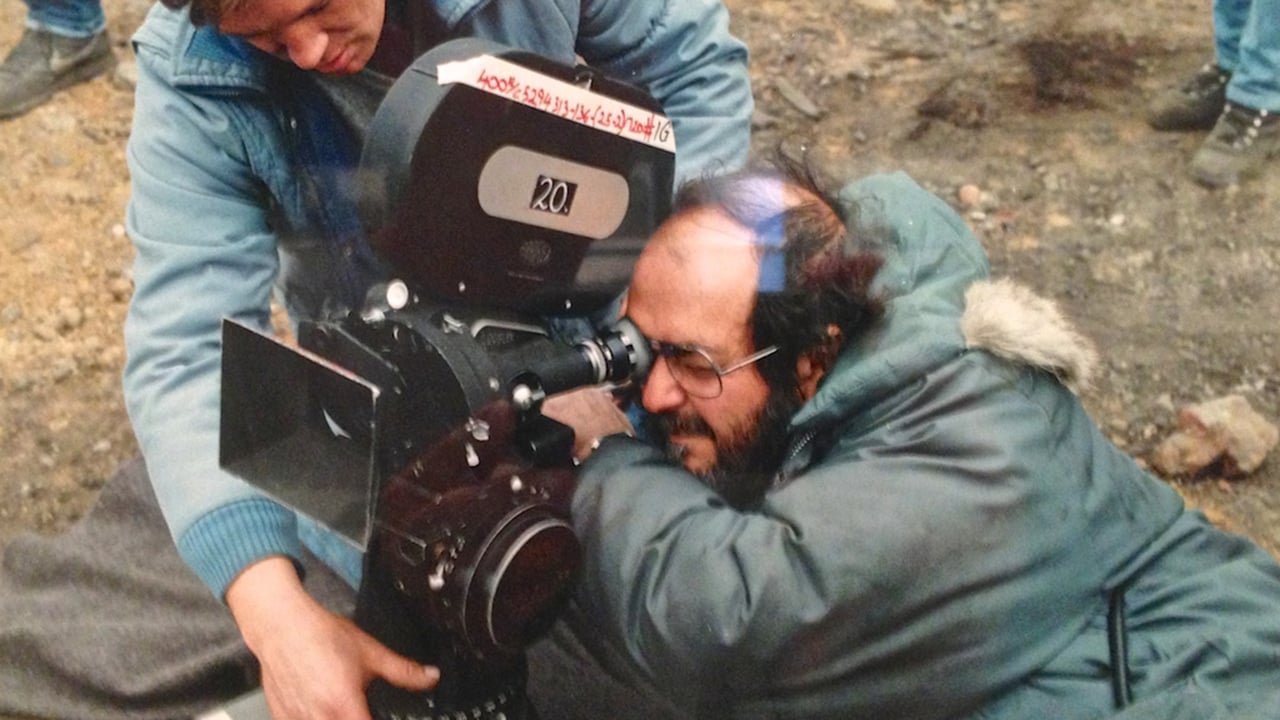

The Arri 35II went on to be the primary camera on Bullit, Easy Rider, Lord of The Flies, A Hard Day’s Night, The Good The Bad and The Ugly, Kes, Clockwork Orange, Deliverance, THX 1138, The French Connection, American Graffiti, Enter the Dragon, and many other important movies, particularly in continental Europe. It was the ‘B’ camera on countless other films, including Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, The Godfather and The Big Lebowski , to name just a few. If you ever see a still of Stanley Kubrick (or, in fact, almost any movie director) hand-holding a camera, it is inevitably an Arri 35II.

The 35II evolved into the 35III in 1979, followed by the 435 in 94 and the 235, Arri’s final 35mm MOS camera, in 2003. In 1952 Arri introduced the 16ST – the first professional 16mm camera with a mirror shutter and the 16mm equivalent to the Arri 35II, and it is 16mm cameras that I will return to in the next part of this story.

The Arri 35II was undoubtedly a landmark camera, but inevitably I have had to leave a lot of other notable cameras out and simplify issues, so please fill in the gaps if you think I have made any errors or omissions in this ongoing story.

Tags: Production

Comments