This isn't about leaving the planet to avoid a zombie apocalypse, but the assumption that we'll always be able to get what we want is increasingly under threat.

I'm not one for conspiracy theories as a first resort for explaining things. Of course, there are conspiracies, but they're not behind everything. I prefer explanations that involve cause and effect based on evidence. It's always a good place to start and is the nuclear fuel of healthy scepticism.

If you've read my typically incoherent ramblings over the last few years, you'll have noticed that I'm a bit of an optimist. I believe in the essential kindness of humanity and that the future will tend towards goodness rather than evil.

I also think that, on balance, technology can be used for good and that its beneficial contributions to civilisation will outweigh its evil ones.

But the changes we've seen over the last couple of years have revealed intrinsic weaknesses in our global technology ecosystem. The current state is not stable, and we need to have a plan B, just in case it collapses.

The camera example

Anyone could have made the earliest cameras with common sense and a bit of light engineering skill. So it's not fundamentally challenging to make a light-tight box with a lens on the front of it.

Today's cameras are brilliant in comparison, but could you make one in your garage? A few years ago, we ran an article in RedShark that said you could. Just order the parts, and you're off to the races. [https://www.redsharknews.com/business/item/1327-redshark-winter-replay-is-the-camera-industry-in-meltdown-or-is-this-a-new-age-for-cinematographers-and-can-you-build-a-camera-in-your-shed]

All of which might be true, but that's not really making a camera from scratch: it's outsourcing the parts. There's no way you or I are going to design and build a new sensor in our outhouse. These are complex light-sensitive silicon chips. They're way more sophisticated than any mechanical machine you can imagine. Very few companies make their own sensors, and there's a healthy OEM trade between the sensor makers and other camera manufacturers. You'd be surprised how often Sony sensors turn up in other camera vendors' products.

Once you discover that you can't just make this stuff, you also realise that almost every device we own has a chip in it. What are the chances of duplicating the skills needed to make an iPhone 13 Pro Max? I'd say "zero" is a pretty good approximation.

Tech shortages

Why am I bringing this up now? It's because we're already amid a chronic shortage of technology. Have you looked at the delivery times for cars lately? Everything that relies on up-to-date tech - and that means advanced processors and memory - is in short supply.

We can look at the reasons for this: unexpectedly high demand post-pandemic; political instability in Europe and Asia; labour shortages; new and un-planned-for trade barriers; skyrocketing inflation - but they all add up to one thing: we depend too much on a continuing supply of advanced technology.

I don't think our ability to make this tech will disappear. But, recent events have been so far outside our comfort zone that we need to have a fallback plan and preferably a fail-over, where we can revert to a previous level of capability gracefully, without too much collateral damage in the process. That's assuming we haven't taken measures to replicate supply capability away from sensitive or unstable areas.

Of course, it's not just the physical capability to manufacture high-tech goods that is at risk: it's access to the intellectual property that exists in areas under threat. Some areas of the world excel in specific fields, and if we were separated from those areas of innovation, it would be hard to catch up quickly. So in this sense, globalisation is a good thing, mitigating the risk of degradation of a single area's capability. There are also plenty of ways globalisation is pretty bad, just for the record!

Beyond the boundaries

During the financial crash of 2008, my friend worked in Amsterdam for a financial software company. Its flagship product could predict trends a split second before competing products and, as a result, gave its customers, who were traders, an advantage in buying and selling. Over time, milliseconds could make millions.

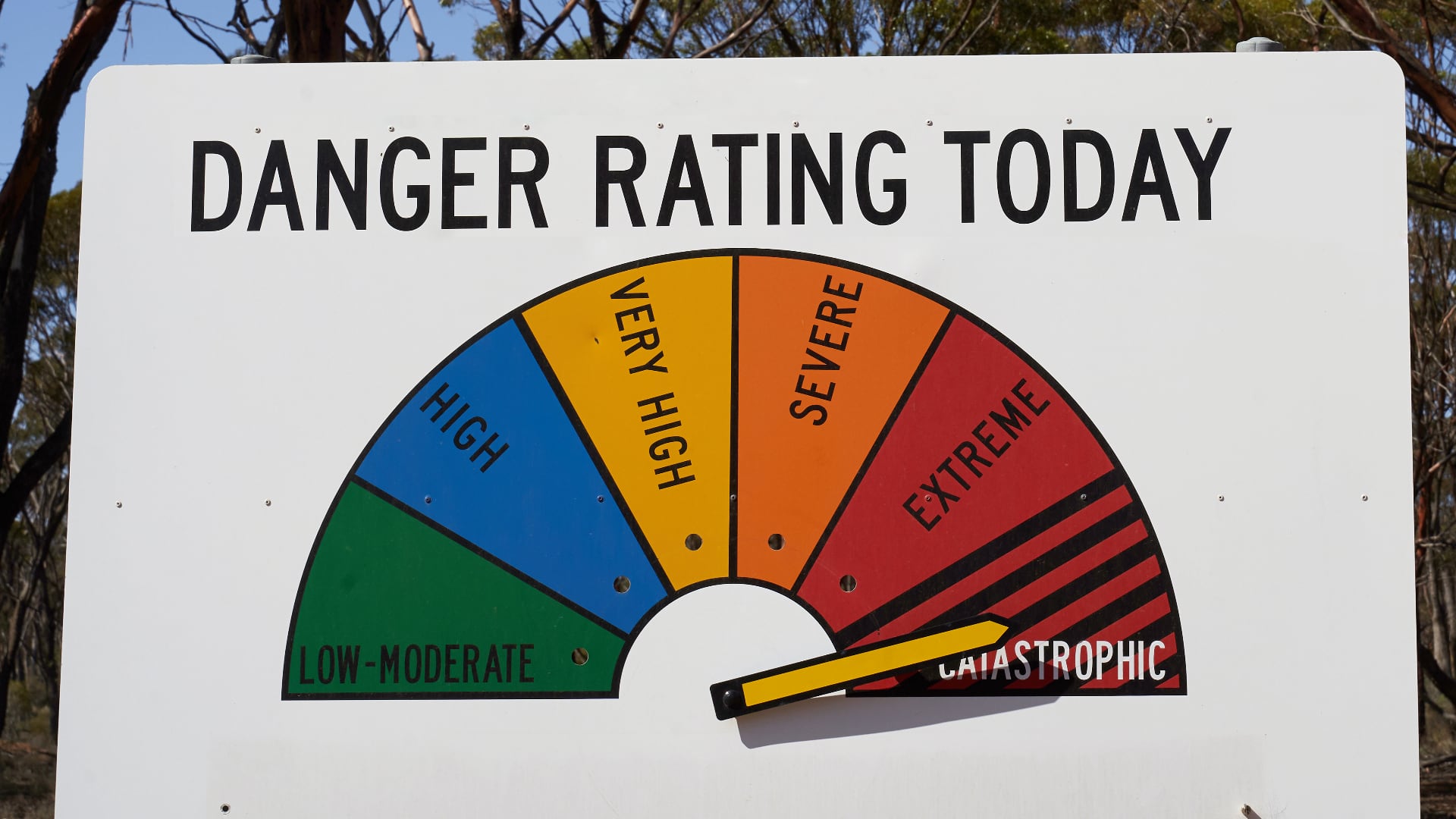

All of that changed when the markets started to go wild. Unfortunately, the software's algorithms only worked in between limits. Designed to cope with almost any expected trading conditions, it couldn't deal with circumstances so wholly unexpected that they were resolutely off the scale. Stocks and shares oscillated so violently and wildly that the software behaved like that famous US suspension bridge that was literally blown to pieces by the wind.

Predictions typically only work within a given set of limits. Our society, politics, economies and supply chains have been operating well outside their "comfort zones" in multiple areas. One factor misbehaving makes it harder to predict outcomes, but perhaps not impossible. But with four or five of them, what you have is essentially chaos.

Have we really reached this stage? I'm not qualified to say, but there is a sense that our "traditional" models; our expectations and our accumulated knowledge - are no longer effective in dealing with the future.

So we need a plan B. We need a graceful and gradual fallback if we're cut off from our high-tech supply.

With some product types, it's relatively easy. Strip the ICE systems out of a car, and there's still a chance it will still work. Ideally, you'd roll back 15 years when cars still had an individual cable for each function. With cameras, a first resort might be the millions of devices lying around because they've become obsolete. If we have to go back to film, It would probably be easier to build a new processing lab than a semiconductor fab.

If we did suffer a massive interruption, we'd need to look much deeper than cars and cameras. It would set medical diagnosis and imaging back decades. There would be no genetically profiled drugs. Industries would suffer, compounding the supply problems, with shortages contaminating the economy.

This is all about scale. There's stuff happening - and poised to happen - that is outside of our preconceived ideas about the nature and scale of change. Part of it is also down to the exponential growth of technology. We wouldn't have so far to fall if we hadn't come so far and so quickly. Many of our assumptions about the future are - rightly - based on the notion that exponential growth will continue. The problem built into this assumption is that the greater the exponential growth, the further askew our assumptions will be when it doesn't happen.

Plan B and more

So how do we deal with this? Well, given that this might be the biggest problem we've ever encountered, I wouldn't want to say I'm the person that has the answer. So I'll merely state the obvious: we need to have plans to deal with an enormous range of possibilities. Covid showed us that it could scupper the best-made plans almost overnight. I'd argue that we didn't have contingency plans in place, not just for dealing with the outbreak and spread of a novel virus, but for how to brace the economy for the impact of such a shock.

So we need to make wider and, yes, wilder assumptions about the future. Let's plan for each one. And have a strategy for those outcomes that no one could have planned for. If you have the resilience to deal with unexpected events, then there will be useful capacity in the system to deal with them even if you don't have a specific strategy.

Let's not put ourselves in a position where there's a single point of failure in our supply chain. Let's always work out multiple ways to solve the same problem. We can still innovate: I'm not suggesting that we should go back to the dark ages. Instead, I'm proposing that we factor in alternative options in all our planning. That will give us many more possible outcomes, and some of those might actually be better.

Tags: Technology

Comments