The best equipment in the world cannot create good stories without a good storyteller at the helm.

Let’s, for a moment, think of all those great movies that would have been masterpieces if only they had been shot with a more advanced camera, or a more characterful lens, or greater resolution or less depth of field or better colour science. All those films that just narrowly missed perfection because of technical shortfalls or out-of-date kit. Can’t think of any? Nor can I.

What I can think of are a multitude of films where although initially intrigued your attention soon fades and, if you do make it to the end, that vague feeling of ‘was that it?’. And I’ve seen far too many indie and student films that are beautifully shot but ultimately simply dull.

To put it in simple terms, what you need is story. You have to want to know what happens next, and that matters because it is happening to a character who is striving to fulfil a fundamental need. That character may not even be human, just human enough for us to identify with.

And, yes, I know there are other traditions of arthouse films that are visually-based and where story takes second place, or structures that are musical rather than narrative, and film artists who reject narrative altogether. But, for the purposes of this discussion, let’s put those aside.

Just how dull can documentaries get?

At the heart of all stories is conflict and, classically, a protagonist who sets out with an aim but comes across various impediments. We may not always be dealing with a single protagonist, but we must have conflict. Wanting to know how a conflict will be resolved is what keeps our attention. And documentaries need drama just as much too.

Despite that, there is a long history of tedious travelogues that have totally ignored the need for dramatic tension; anyone old enough to remember the formulaic shorts (‘Quota Quickies’) that appeared in British cinemas up until the mid 80s, funded through a tax on ticket sales to subsidise a British production quota, will know just how bad short documentaries can be. One British filmmaker, Harold Baim, produced over 300 35mm shorts to fulfil this need. Some, like Telly Savalas Looks at Birmingham, have now achieved cult status for their dullness, devoid of charm or irony. Thankfully, that is all in the past. Or should be.

It is easy to find today to find examples of carefully made and decently shot short docs that set out to make a ‘portrait’ of a person, a place or an institution which fail to really engage because there is no tension and thus no story. An interesting subject is just not enough.

Characters must want something

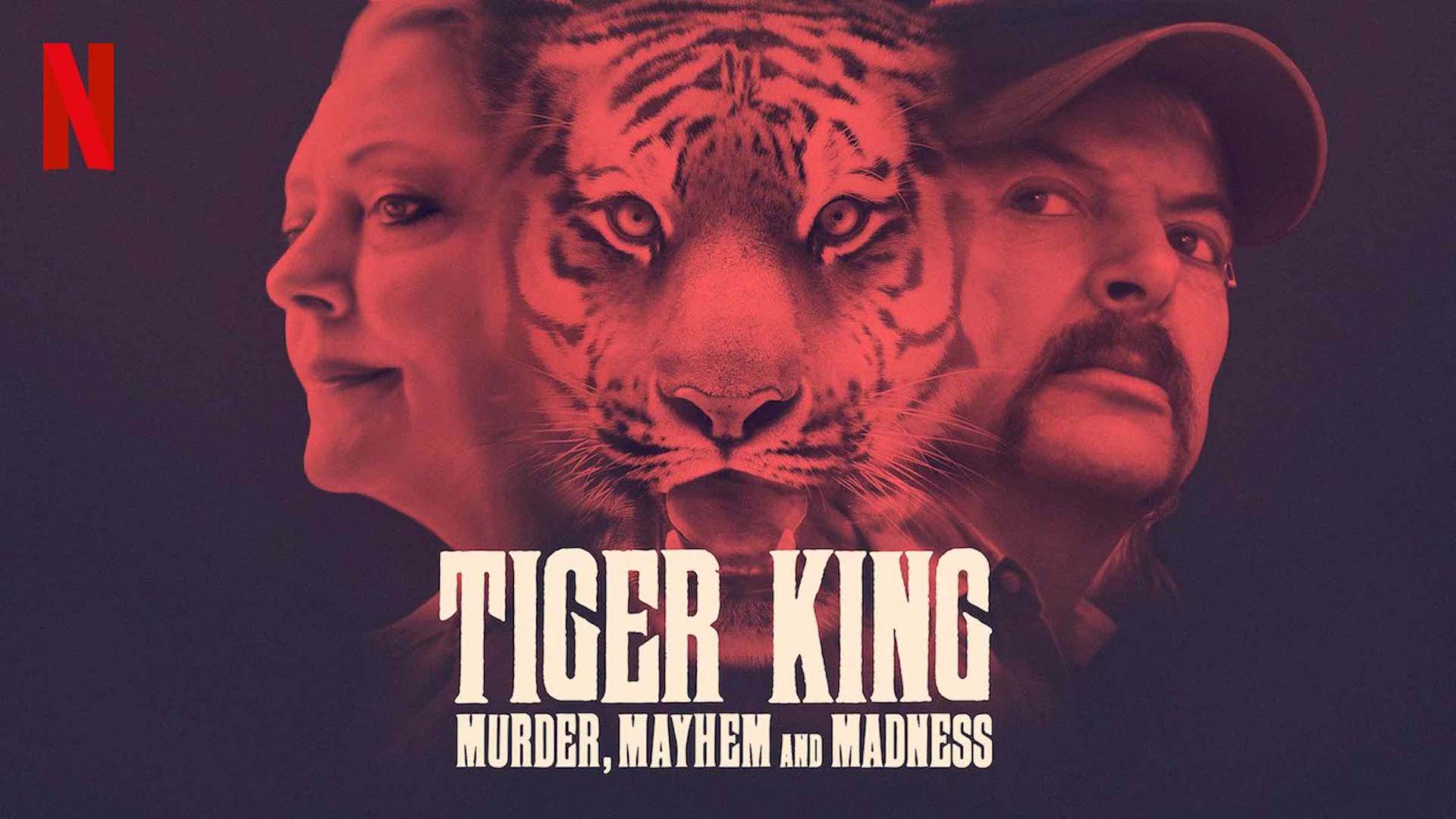

Characters are 'wanting' machines. Characters need to want, preferably yearn for something, but life gets in the way. And we root for characters, even if they are fundamentally unlikeable, when something unfair happens to them (HBO’s Succession is a prime example of this). We are drawn to dreamers, particularly flawed dreamers. Look at Netflix’s phenomenally successful Tiger King: Joe Exotic is a mess, a vindictive egotist and an abuser of wild animals, and yet you are drawn to his naïve ambitions and the fact he appears to be a victim of more ruthless people. And of course a big question at the centre – was he guilty of attempted murder?

We can even identify with psychopathic killers when their well-made plans go astray (plenty of examples in the work of Alfred Hitchcock and Patricia Highsmith and, more recently, in Netflix’s You). Identification does not mean you approve or even like the character, just that you get sucked into desires and frustrations of their world.

Passive characters, who are happy to accept whatever comes to them, do not make good protagonists, however decent they are as human beings. Before you send me examples of great works where the central character merely observes, I defy you to name a really successful movie or TV show which is not driven by humans striving towards a goal, whether that be to solve a crime or find a missing person, or for riches, revenge or just survival.

Current affairs need it too

The BBC’s One Upon A Time In Iraq series has, deservedly, won many awards. What makes it special are the individual characters, from all sides of the conflict, telling their stories in a carefully lit studio, well dressed and relaxed, contrasting with the ragged war footage. What the series does beautifully is to present the characters’ hopes and desires: for peace, to return to their family or to save lives or, for those who fought in the conflict, to make sense of the pain and suffering and believe it was worthwhile. We probably don’t like the Rambo-style soldier, but we do get a sense of how his whole sense of self and reality was torn apart. The conflict is deep inside him.

Return From ISIS: A Family’s Story, (winner at this year’s Rory Peck awards) is about an American family who end up in Syria. At the heart of the film is whether Samantha, the mother, was forced against her will to work for ISIS or whether she was a willing accomplice, fully aware of what she was getting involved with. Her need for survival, for herself and her family is obvious, but were there other, conflicting impulses here? Did she yearn for adventure, to escape small-town America? Did she need to please her husband? Was she even drawn to the ideology of a ISIS?

For many, everything I’ve said above might seem obvious. Nevertheless, I keep seeing dramas where the central characters don’t seem to want anything, and documentaries devoid of tension.

Tags: Production

Comments