Replay: Forty-eight years ago, in 1975, a device was invented that changed the face of cinematography. It was called the Steadicam, and it is still keeping pace today, even in a world full of gimbals.

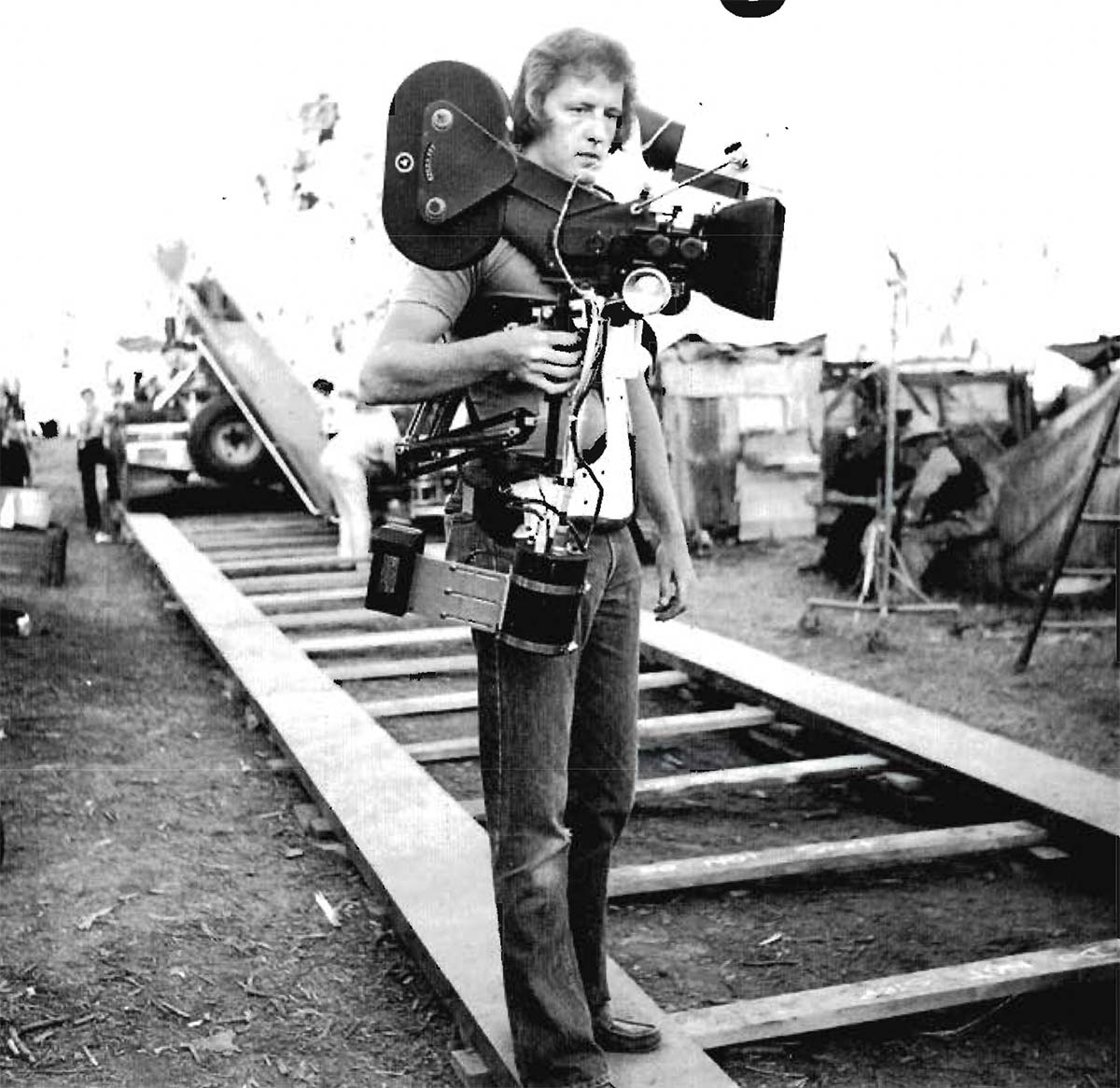

When Garrett Brown first used his Steadicam invention on the film Bound for Glory, it was clear that moving a camera on set was never going to be the same again. Even now, that first early Steadicam shot holds up as a stellar example of what can be done with the device. It even won the DP, Haskell Wexler, an Academy award for Best Cinematography.

Further iconic uses followed in films such as Marathon Man and the famous stair climbing scene from the training montage in Rocky, further cementing it as a system that could achieve previously impossible shots.

Garrett Brown with his original Steadicam on Bound for Glory.

The Steadicam begins to evolve

The first significant evolution of the Steadicam came when director Stanley Kubrick required a floor level shot in The Shining. He demanded that the camera be situated only just above the ground. Until that point the lowest angle that could be achieved was around waist height, so Garrett developed a 'low mode' for the system. Low mode inverts the main post so that the camera plate is upside down. A new mounting system was required to bring the camera itself to the correct orientation, but it brought yet another creative tool to the Steadicam's toolbox.

Iso-elastic arms

While the Steadicam itself improved its design over the years with smoother arms, better payload capacity, and better vests, it also spurred competitors, including Panavison's Panaglide, which went on to be used extensively on many a Hollywood movie, including John Carpenter's Halloween, despite disputes with Cinema Products, which owned the Steadicam brand at the time. Rumour has it that Panavision actually destroyed the Panavision sleds eventually. If you want to know more about the Cinema Products vs Panavision story, as well as other systems you can read Garrett Brown's account here.

Copycat systems were always going to be a problem for such a revolutionary device like the Steadicam. Although as you'll see, competitors have also spawned some rather significant developments of their own.

However, one aspect of the Steadicam design that Garrett changed, which is still very effectively protected by patents, is the iso-elastic arm.

A modern Steadicam G50X arm. Image: Tiffen.

Iso-elastic arms were, and probably still are, one of the primary aces up the sleeves of the Steadicam that has separated it from the many copycats over the years. Iso-elasticity allows the Steadicam arm to be set at a certain height, and it will stay there. Current arms achieve this by varying the spring geometry.

Traditionally, if you wanted to, say, get a higher angle shot, you would have to manually lift the arm to that height, otherwise it would want to return to its default height, usually waist level. You could set the preload, and this would increase spring tension to lift the rig to a higher default resting spot, but this not only affected the damping of the arm, introducing potential 'bounciness', but it also restricted you if you also needed to go lower during the shot due to the higher spring tension.

Iso-elasticity lets you set the 'ride height' for the shot you are taking, and the arm will stay there without the need for extra force. Tiffen's iso-elastic designs also stay constant in the amount of force required to maintain them at different heights, usually only requiring a light touch.

This not only makes the operation less fatiguing it also drastically reduces the chance of unwanted movement from the operator's arms being introduced into the shot. Interestingly the arms can also have the amount of iso-elastic behaviour adjusted as well, so operators who prefer a more traditional feel can achieve that if they prefer. Heathens.

It should be noted that the older 3A and similar style arms were kind of iso-elastic towards their maximum payloads, but became less iso-elastic in their behaviour as the load lightened. Although there can't be many operators who enjoyed using a maxed out rig like this on a regular basis.

Alternatives

Whilst no other company could manufacture iso-elastic arms, the original non iso-elastic style arm design was finely refined over the years by different manufacturers. One of the most respected of these is the GPI-Pro system, and it would be wrong not to mention it here. Some operators even prefer it. The GPI arms can have their maximum payload adjusted by using interchangeable spring canisters. So a semblance of iso-elasticity can be achieved with the right canister/camera combination. I've never used a GPI-Pro personally, so if anyone can offer further insight I'd love to hear it.

Once again, things stayed fairly static for a while in terms of major developments. Rival companies to Tiffen, who now own the Steadicam brand, developed different systems such as the Alien Revolution by MK-V, which created a boom arm attached to the stabiliser suspension arm and contained a motorised head that could rotate the camera through 360 degrees on its longitudinal axis.

The MK-V Omega Revolution head. Image: Shutterstock.

The Alien Revolution or AR system, lets users operate the rig at any angle to the body, as well as being able to seamlessly transition between high and low modes. For example an AR operator could co from floor level and make the camera follow the contours of a car, flying the camera over the top of it. Something that isn't possible with a traditional stabiliser. The AR system has now been replaced with the Omega Revolution system. While MK-V is a rival manufacturer to Tiffen, it is important to mention the additional operational creativity the AR system brought to the table. Today the ARRI Trinity system is an alternative to the AR design, being capable of very similar moves but with the addition of a tilt axis for even more versatility.

Enter the gimbal

The largest threat to the existence of Steadicam came with the introduction of inexpensive motorised gimbals, or so many people thought. The truth is that a Steadicam still offers many advantages over a gimbal in the hands of experienced operators, but that's not to say that developments have stayed static. In fact, gimbals have influenced what is possibly the largest range of innovations so far.

In the sphere of the high end, a huge development was the introduction of the Steadicam Volt. The Volt isn't a gimbal as most people know it, but it does offer assistance to Steadicam operators in terms of keeping the horizon level.

The Steadicam Volt. Image: Tiffen.

One of the most difficult parts of operating Steadicam is keeping a level horizon, particularly when countering momentum through corners, operating in windy conditions, or when fast post rotations are required. Likewise, when slow movements are performed or when the rig is being brought to a standstill at the end of a movement, the horizon can be tricky to keep level.

The Volt assists the operator by keeping the horizon level or a set roll level and maintaining a tilt angle if required. It can also smoothly return the camera to the preset angle without the rig pendulating.

It's a clever system that attaches where the traditional post gimbal used to be, meaning that there's no real extra bulk or weight to the system. In fact, you have to look closely to see that it's there. It can also be retrofitted to older systems such as the Ultra2 and Clipper3 models, which have been around for a fair old while now and long since discontinued.

This highlights one of the beauties of Steadicam systems. Because they are generally semi-modular, innovations like this can still be utilised even on older equipment. Interestingly, Tiffen will also be making Volt compatible with the GPI-Pro systems.

Speaking of modularity, Tiffen now has its M-2 system, which has been designed as an entirely modular design. Recently it introduced a Core kit to allow users to build up the system in stages. Don't misunderstand, this isn't a bargain basement way of getting into Steadicam. It still falls firmly into the "if you have to ask, you can't afford it" category, but it is at least a system that can be built in stages.

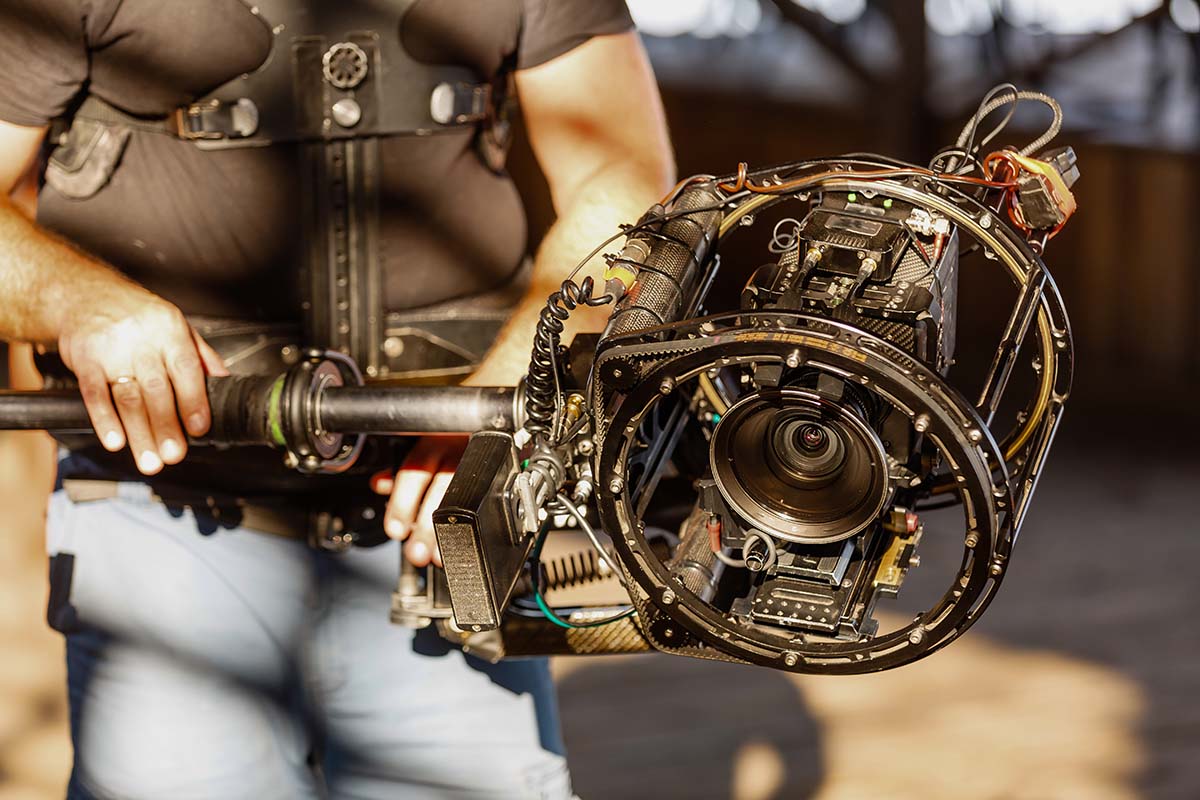

Acknowledging gimbals

Tiffen hasn't ignored gimbals, however. It is also possible to adapt 3-axis gimbals to a Steadicam arm, and it makes a lot of sense. Operating a gimbal by holding it unsupported for long periods, particularly with a heavy camera, is not great for your body, even if you think it makes a good workout. The Steadicam-S system lets users attach handheld gimbals to a Steadicam arm system. There are more advantages to doing this than just fatigue reduction, however. By using a Steadicam arm, the 'walkiness' of many a gimbal shot can be reduced or eliminated more easily than with the gimbal alone.

The skill of operating a Steadicam or equivalent system to a point you can charge for doing it remains a difficult bar to achieve. I'll make no bones about it, the dedication required to become good enough to charge for work is large. However, with smaller, lightweight rigs available, as well as methods for adapting gimbals, would-be operators now have a slightly easier route in that people in the past. On the high-end, it is now possible to perform the sorts of impossible shots that even Garrett Brown wouldn't have thought possible back when he first debuted the system in 1975.

It would be easy to say that recent developments and the affordability of gimbals has dulled the appeal or practicality of the Steadicam and other, similar, devices. But the fact is that, aside from very low budget productions, if you want the best stabilisation, nothing really comes close to having an experienced Steadicam operator on set.

Whilst I have tried to produce a potted history of developments here, I'm sure there are RedShark readers who are immersed in the world of Steadicam, who can offer their insights in the comments below, particularly if you know what really happened to the Panaglide rigs.

Comments