Replay: Part One of our six-part series looking at the history of VFX starts back with early pioneers such as Georges Melies developing the optical effects that Orson Welles would use to such dramatic effect nearly half a century later.

While a wide variety of devices had been invented that projected moving images in one way or another to an enthralled public as early as the 16th century, cinema itself is widely regarded by most celluloid historians to have begun in 1895. It was then that the Lumiere brothers showcased their first successful method of both filming and projecting moving pictures in Paris, the Cinematographe. And given the long and glorious role that VFX have played in the evolution of cinema since, it's not too surprising that the first special effect was created not long after.

The French effects pioneer Georges Melies is widely credited with the first stop action shot, and he certainly did stumble upon it independently, but It was Edison camera operator Alfred Clarke who got there first, deliberately pausing his shot and substituting a dummy for the body of an actress during a scene recreating the beheading of Mary Queen of Scots. The date was 28th August, 1895.

Melies' independent discovery of the same technique may have been an accident — famously his cameras handcrank jammed and took around a minute to get going again by which time the street scene he had been filming changed completely – but he certainly took that happy accident and ran with it, effectively becoming the world's first impresario of effects films.

In films such as Indian Rubber Head (1902) and the 21 minute epic (for the time) A Trip to the Moon (also 1902) he pioneered a range of VFX techniques such as the split screen / double exposure process, and was very much part of the European movement that saw film as a loose narrative joining together special effects sequences. This was eventually to prove his downfall as audiences started wanting more sophisticated, narratively focussed fare, but over the course of 500 titles and 10 years he pushed the technology as far as any individual in the early period.

Model Hollywood

Meanwhile, in the US, news films were recreating scenes from real life events with the increasing use of models for growing audiences. These saw the development of classic practical effects - explosions created using gunpowder, burning cardboard buildings shaking in earthquakes, wooden models pulled along by string, water pistols recreating the jets from a fire hose and so on. They weren't very good, as a generation of craftsmen, technicians and money men all grappled with the new technology, but the audience's tastes at the time were equally undemanding.

By the 1910s, however everything had started getting a lot more sophisticated. The first VFX specialists started to appear (though they wouldn't start getting credits until the mid 1920s) and pioneered the use of techniques such as using glass mattes for scene extensions. Industry giants like DW Griffith also started developing the visual language of film using techniques such as shot transitions, iris-in and iris-out for dramatic effect, and so on.

The 1920s saw Hollywood really get into its stride, with extensive use of model effects in particular in historical epics such as Ben Hur and the Thief of Baghdad, while Cecil B deMilne led his Israelites though sliced walls of double-exposed jelly to simulate the parted waters of the Red Sea in The 10 Commandments. But the '20s really belonged to the Germans, who were streets ahead of their American counterparts in technique and execution, and in particular Fritz Lang's astonishing Metropolis (1926).

The shape of things to come

The film is still visually stunning nigh on a century later, Lang throwing all of the top technologies of his day at the project and using matte painting, rear projection, compositing techniques, and pushing the art of miniatures further than ever before to make the animated cityscapes of the film's impressive opening sequence.

It was also the first film to successfully use the in-camera, optical technique invented by Eugene Shuftan, the Shuftan process. This used a combination of angled mirrors, paintings and live action to create the impression of live actors occupying huge sets, and is essentially seen as a primitive precursor of bluescreen. Certainly it helped give Metropolis the sense of scale which is a hallmark of the film and a central metaphor for the alienation of the individual.

The 1930s are perhaps best characterised as a decade of cautious progress. Rear projection, travelling mattes, miniatures…all these techniques saw steady development, with rear projection especially becoming popular due to the demands of the primitive new audio technology of the 'talkies' making location filming nigh on impossible. As a result, by the end of the decade, rear projection screens as large as 14.5 m were in use, with the key to success being matching both the lighting and the focal lengths of background and studio camera exactly.

The introduction of optical printers around this time led to huge improvement in image quality, especially when combining the disparate elements for travelling matte work. If you're looking for touchstones from the decade, King Kong probably stands out along with many of the horror movies made by Universal Studios, with the highlight from that canon being the creative use of the Williams process to achieve the invisible scenes in The Invisible Man (1933). This essentially involved filming an actor wrapped in black velvet with an airtube running up his legs against a black velvet draped set to get the images of his empty clothes walking around. These were then copied to high contrast film in a complicated process involving multiple sandwichings of exposed and unexposed film.

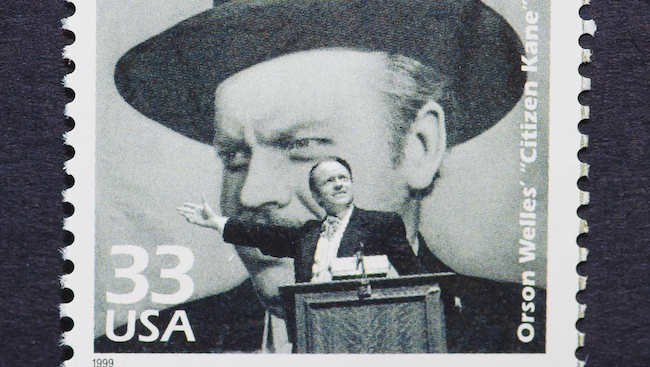

By the time we get to Orson Welles' classic Citizen Kane (1941), you have a film that was reliant on special effects to tell much of its story, but also one that was not even nominated for an effects Oscar as the majority of them were invisibles. However, it took many of the VFX techniques of the day to their absolute limits, combining matte paintings, miniatures and optical printing techniques in particular to produce Welles' final masterpiece. Add in unconventional lighting, strange camera angles, deep focus shots elaborate camera movements, extremely long takes, non-linear storytelling, and the first appearance of many of the editing conventions that would become part of the filmmaking repertoire for decades to come, and you have the last great movie of the early days of film special effects, and undoubtedly one of the greatest all time.

However, it was 1941, war raged across Europe, and for the still embryonic visual effects industry, colour was about to change everything.

Part 2 of The History of VFX is here.

Tags: Production

Comments