Can you build a camera in your shed?

Can you build a camera in your shed?

This holiday we're re-running some of our most popular articles, in case you didn't see them the first time. Today: Electronics is so completely integrated now that building new equipment is just a matter of glueing together a few parts you can buy from the Internet. Is this true? And is this the biggest threat to traditional camera manufacturers? In this article, we investigate this, and the background to it, in detail

The apparent demise of Aaton in the last few days is a milestone on the way to... what, exactly? The total destruction of the industry? Well, seemingly no, because many content creators are saying that this is the best time ever to be behind a camera - especially if you have a limited budget.

As I said in this article shortly after RedShark started last year, "We're living in an extended period or rapid change". Quite simply, everything is changing, and with each passing day, year or nanosecond, the rate of change is increasing.

What this means is that whole industries can find themselves without any customers, because something better and different has appeared, sometimes overnight.

Consider the 19th Century

Back in the 19th century, cars didn't wipe out the horse and cart industry instantly, but they did eventually, and comprehensively. There was no point in inventing a better horsewhip when the same investment in better tires or engines would be appreciated by an increasing, as opposed to diminishing, buying public. And who cared about better cassette recorders when MP3 players were taking off (and who cares about MP3 players when you can have Spotify?).

This stuff comes in as if by stealth. A $1200 external ProRes recorder can accomplish much of what an HD tape deck costing twenty times as much could do, except that it's fifty times smaller and is also non-linear. And it can run on batteries. In the face of such change, how does an industry adapt and survive?

The demise of film is perhaps the starkest illustration of paradigm change. There will always be those who hanker for the analogue look and feel of film, with reason, because it had a quality all of its own; but the debate is no longer whether digital can exceed film in quality, but by how much? And - in a nuance even more subtle than that - whether it is actually necessary to make the quality is better now that we've reached such a high level.

Supersonic

Developing a product in this environment is so much more than the already very tough process of conceiving, designing, nurturing and manufacturing a new product. If, in days past, that was a stroll across the street, today's process is like climbing out of an aircraft at supersonic speed without a parachute or air supply, and leaping onto another aircraft that's passing below you - at five times the speed.

Well, it is like that if you look at things in "old world" terms.

And I suspect that this is what Aaton were trying to do. Trying to ride out not only a change of paradigm but a change of culture, they designed a product that on paper and in practice was extremely credible, with great-looking images and a form factor that seemed right to a lot of people. The Aaton Delta Penelope was a big camera with large, silent fans, that included just about everything you needed to get going.

Now, without going into Aaton's financial situation too much, you can see why their digital product might not have been a fantastic success. It’s because there are industry giants who have productised and marketed their ideas first. These are big companies who have the financial buffer to ride out the initial storm caused by the change from film to digital. The likes of Sony probably waited until the moment was right before they brought out their F5 and F55 which are at least arguably their responses to the RED Epic.

And then there's Blackmagic, with their extraordinarily secretive program to develop a range of cinematic cameras at a price that - at least at first-sight - is simply unbelievable.

So does this mean that we've seen the last innovation in this close-to-saturated field? No, not at all. But only if you "get" what's causing all this progress in the first place.

Today's level of integration

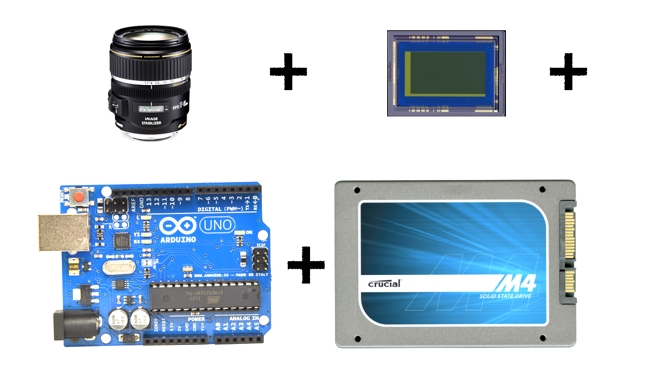

What makes today different from any other time is the level of integration in today's electronics. Here's what I mean.

Let's say that you want to design a cinema-type camera. Which means it has to have a resolution of around 4K, must have at least 13 stops, and be compatible with most modern (and ancient) lens-mount standards. And it has to have a neat, functional industrial design with a capable, flexible, connected operating system. The UI needs to look good as well.

That's a lot of work if you intend to start from stretch, but the point is you don't have to start there: you actually start about 98% of the way down the track.

You see, most of this stuff is available off the shelf. All you have to do is design the look of the product, write some "glue" software, and you're up and running. Don't believe me? Well, this is how it would go.

First, find a sensor. Aptina have recently produced a great-looking 4K sensor that's compatible with standard electronics. You might think that Canon and Sony have the lead in this type of thing because they make their own sensors, but that doesn't stop other companies specialising in ONLY sensors (which is what Aptina does) and because they specialise, they're actually pretty good. (You'd probably want to define anyone that supplies Nikon with sensors as "Pretty Good").

Then add some storage. There are lots of choices, with many options fast enough to store 4K RAW video.

Glue electronics - yes, complicated, but well understood, and you can fit it into a FPGA - which is software-configurable hardware. Essentially whatever it is you've built wakes up and thinks it's a toaster, but as soon as it loads up its firmware, it can behave like almost any type of logic-based processor. Programming FPGAs is no trivial thing, but there are quite a few experts around now so you would rarely have to start from scratch, and FPGA vendors like Altera build in already-working modules to deal with SDI, HDMI etc.

An operating system and UI? Well, for a modern camera you'd need plenty of processing, wireless connectivity, network connectivity, a touchscreen, and probably GPS and accelerometers as well. So you've be able to build a connected camera with a modern interface that would know where it is and quite possibly have some type of image stabilisation based on the output from the built-in accelerometer and gyroscope.

All of this might sound like a lot of work, but it isn't, really. You can buy Android boards that have virtually all of these capabilities (because, let's face it; smartphones do), and all you have to do is essentially write an Android App that is your User Interface. It would probably be pretty stable too, as people tend to update the software on their cameras less often than smartphone users. If you don't want to use Android there are plenty of other options, including the Raspberry Pi, a Linux computer that costs much less than a tank full of petrol.

This is pretty much what Blackmagic has been able to do

This is pretty much what Blackmagic has been able to do, in a very slick and clever way. They've taken certain parts off the shelf, integrated them, wrapped an excellent (if controversial) industrial design around it, and called it a product. I don't want to minimise their efforts here, which were extreme and spot-on, but probably the bulk of the R&D which they have done has probably been around the macro-level rather than a micro one. Their skill has been strategic, and they have wrapped software, support and distribution logistics around their new products to create an end-to-end ecosystem for building and selling cameras whose performance defies belief in their price. (Note that when I say “off the shelf” this doesn’t mean they’re buying a shrink-wrapped item. As we have seen with Blackmagic and very recently with Aaton, as a product integrator, you still have to deal with quality and supply issues when dealing with outside suppliers. You're also at the mercy of your suppliers, because if they decide to end-of-life a product that's intrinsic to your design - you have to redesign!).

So does this mean that we'll see a rash of new cameras conceived and designed in a garage? Not necessarily. The camera field is getting pretty full now. But what we might see instead is, what, exactly?

It's impossible to say. The very high end vendors will keep doing what they and their customers absolutely love - very high resolution cameras with utterly dependable performance. It's worth paying that bit extra when each minute that you're paying the talent probably costs more than the camera itself.

We'll see all types of innovation coming absolutely out of the blue

But at other levels, we'll see all types of innovation coming absolutely out of the blue. It is in the nature of exponential growth to produce surprises. The steeper the innovation curve, the harder it is to predict what's coming next. As little as two years ago, 4K would have been an outside bet as a consumer phenomenon. Now it's a certainty. The only surprise with it is how quickly it's happening. To paraphrase RedShark contributor Adam Wilt: We knew that 4K would be big, but it's a surprise that it's this big, this fast.

Perhaps the best illustration of integration is the smartphone app. As we've already mentioned, Android development boards have just about everything built in. What would in times past have been an expensive development project, is now just an API call (in other words, if you wanted to know your GPS location, you've have had to design a GPS system from scratch. Now, you just say, essentially "GPS: Tell me what my position is", because it's all built in already).

Each generation of tools builds better tools for the next generation

Each generation of tools builds better tools for the next generation. That's why everything's getting better all the time. On top of that you have to add increasing connectivity, faster bandwidth, faster processing, faster and bigger memory, and, bringing it all together, software that's better able to make this most of all of this. When you look from the top to the bottom of this technology stack, you see ultra-HD cameras that can all contribute to a panoramic, stitched-together picture. At some point the whole globe will be one moving version of Google Maps. And then, Big Data will take over, drawing conclusions from the billions of inputs that it has. (If you think that's unlikely, what on earth do you think Google is doing with Google Glass?).

Quite what all this means for content production and for what people like us will do as we consume it, remains a matter for speculation. In a way, that's the whole point. As users, we just have to wait and see. But as manufacturers, we have to try to predict opportunities and take them as robustly and as quickly as we can. If we're lucky, we'll succeed in turning a whole industry on its head. If we don't get it right, we could end up with a warehouse of products that our customers were demanding yesterday, but simply don't want today.

But what does all of this mean for traditional companies with traditional skill sets? To put this another way, do companies that have been building film cameras for decades still have what it takes to build modern digital cameras?

Well, it depends on how you define a camera.

The days of film

In the days of film (remember them?), what a camera didn’t do was contribute to the “look” of the image, or, perhaps, only peripherally. The actual quality of the picture came from the film itself, which was not part of the camera. That’s the biggest change of all in the new digital paradigm: that the camera manufacturers are now responsible for this look, where “look” includes just about everything to do with the image: contrast and dynamic range, colour, sensitivity, highlight response and a myriad other parameters that can affect the output from the device. It’s only the lens-mount and a few other light-domain aspects of the camera (such as whether it has a mechanical shutter or not) that can be extrapolated from previous film-based designs.

The biggest common link between these two eras? Ergonomics. The human form hasn’t changed as we’ve gone digital, so the ergonomic needs of camera operators are approximately the same. So it’s reasonable to think that older camera vendors will know a thing or two about this.

But most of the skills you need for the digital domain are... digital. If you’re going to build a digital cinema camera, then you need to know how to take the raw image off the sensor, and process it so that you get the best possible looking output. Of course a lot of this is done off-board in a raw processing workflow, but there’s stuff going on inside the camera that only those in the deepest inner circles know about. So at the very least, if you’re putting together a camera “off the shelf” you need to recruit some image processing experts as well.

One source of expertise is just “out there”, on the internet. It’s a model that can work, sometimes, with software. Open source development depends on the willingness and capabilities of those taking part, but it can lead to very substantial achievements like Blender. There are even tentative steps into Open Source hardware with Arduino and the camera project Apertus.

Business

Even if you can build a camera - and the chances are that if you know what you’re doing, you will be able to; you still have be able to run a business. And that’s where the likes of Blackmagic and RED have a distinct advantage: They’re young and immensely flexible, proven in the world of high-tech business, and able to turn ideas into reality in a short time. And they're able to market them extremely well to an eager audience.

Tags: Business

Comments