Pairing lenses with different mounts

Pairing lenses with different mounts

RedShark Replay: The problems of fixing lenses to mounts they were not designed to use.

As cameras have improved hugely in price-performance ratio (and lenses conspicuously haven't), the pressure on lens availability has been enormous. This creates a need to combine lenses and cameras that weren't necessarily designed for each other. Since lenses are a long-term investment, their potential for compatibility with various cameras can be a very big deal.

Critical distances

The fundamental purpose of a lens mount is to hold the optical assembly – the bits of glass – at the right distance from the sensor. Anyone who's played with a magnifying glass and a piece of cardboard will be aware that it's quite easy to project an image of a nearby desk lamp or window onto the cardboard. The critical thing, though, is the distance between the lens and the projection surface. That distance is very critical – much more critical, in fact, than the distance between the lens and the subject.

In a practical camera, the focal relationship between the lens and the sensor must usually be maintained to within microns. If correct distance is not achieved, the focus scale on the lens will become inaccurate and it may be impossible ever to achieve infinity focus. The distance from a specific point on the lens mount to the sensor (or film) is the flange focal distance, and it is a crucial factor determining how various lenses fit, or can be made to fit, on various cameras.

Sony's E mount, for instance, places the lens mounting flange 18mm in front of the sensor. Canon's EF mount, on the other hand, is designed to place the lens 44mm in front of the sensor. The difference is largely down to the fact that Canon designed the EF mount to leave room for the viewfinding mirror in a true DSLR camera, whereas the E mount is designed solely for electronic-viewfinder cameras. Similar concerns apply to the popular micro four-thirds mount, which was likewise designed to allow for physically compact mirrorless cameras (the original, non-micro 'four thirds' mount is more generously specified, to leave room for a mirror).

Adaptor possibilities

As well as defining how the mounts work with native lenses, these mechanical concerns place limits on what can and cannot be achieved with adaptors. It is impossible to use (for instance) a micro four-thirds mount lens on an EF-mount Canon camera using a purely mechanical adaptor. The micro four-third lens is designed to be placed close to the sensor, but on a Canon camera, that space is full of other camera parts. Adaptors exist which make this sort of thing possible, but they must include lenses designed to adjust optically for the new flange focal distance (and possibly to correct image size, telecentricity and other problems, too).

Mount adaptor to suit B4-mount broadcast zooms with corrective optics

Mount adaptor to suit B4-mount broadcast zooms with corrective optics

It's for this reason that companies such as Blackmagic sometimes choose the micro four-thirds mount for their cameras and probably why the Sony FS7 uses the E mount. It's not that there's anything particularly special about these mounts. In fact, they're fairly lightweight, risking misalignment of those crucial dimensions when used with heavy lenses. The reason they're used is that they have a very short flange focal distance, which means that adaptors can be built to allow compatibility with a very wide variety of lenses. An owner-operator might consider buying a camera in a mount that doesn't directly suit any lenses on hand, simply because mechanical adaptors are reasonably affordable and the flexibility to use others is an attractive bit of future-proofing.

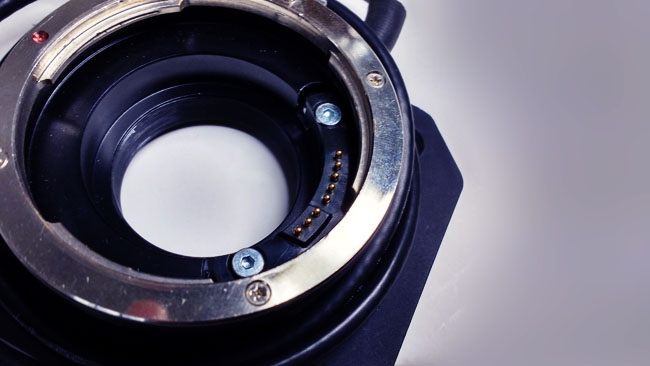

Now, these compatibility concerns are purely mechanical; there are other problems with some lenses, particularly Canon EF and EF-S types, which offer iris control only through a proprietary electronic control system and can be hard to use without a compatible, electronically-active mount (companies such as MTF Services have a solution for this).

MTF Services has mount adaptors with electronic controls for Canon EF lenses

MTF Services has mount adaptors with electronic controls for Canon EF lenses

From a purely mechanical point of view, though, mounting a lens on a foreign mount is largely a matter of having space to put some supporting metalwork inbetween the two. There can be other glitches, particularly that some lenses have components that protrude backward beyond the flange point. These can cause trouble with DSLRs and optical viewfinder movie cameras which have a spinning mirror behind the lens; it's possible, for instance, to re-engineer a Canon 7D with a PL mount, to accommodate movie lenses, but some lenses can physically collide with the inner workings of the camera.

Toughness

The other concern with lens mounts is sheer physical strength, especially with big cinema lenses or on cameras which might be used off the shoulder, where a handgrip on the lens forms a critical part of the camera support and the mount must accept a significant load. While it's possible to mount huge broadcast or cinema lenses on DSLRs, mounts intended for small, lightweight stills lenses can struggle to cope and, if there is any instability, it can lead to visible focus problems because the flange distance is so critical. Particularly, there's a key difference between bayonet type mounts and the breech lock mounts used on broadcast cameras (with B4 mounts) and those intended for cinema applications (mainly PL mounts).

Bayonet mount typical of DSLRs and lightweight cameras

Bayonet mount typical of DSLRs and lightweight cameras

A bayonet mount is found on almost all DSLRs, where the lens is inserted then twisted. Conversely, a breech lock lens is simply placed in the open mount, with the two critical surfaces in contact, and a locking ring rotated into position and kept there by friction. The latter approach involves less wear on the critical surfaces, which aren't required to slide against one another, and tends to be made out of comparatively massive pieces of metal, whereas DSLR mounts are size and weight constrained.

Breech locking mount to suit B4 broadcast zoom

Breech locking mount to suit B4 broadcast zoom

So yes, it is possible to put an adaptor on your Pocket Cinema Camera (weight, about a third of a kilo, with battery) and mount a massive, multi-kilogram anamorphic zoom on it. You will, of course, need to mount the lens carefully on a set of rods first, and allow the camera to dangle from the back of it – but it can be done. And yes, you can also, if you really like, mount almost anything on your Canon 5D Mk. III, but you may end up paying significantly more money for optical adaptors to correct for Canon's long flange focal distance. That's before we've even considered how large an image each lens projects and how adequate that's likely to be for any given camera. Unfortunately, given the variability in the size of sensors that various manufacturers consider to be 'super-35', for instance, that'll have to be a subject for another day.

I'm indebted to Mike Tapa of adaptor manufacturer MTF Services for access to the lens mount adaptors used to illustrate these articles.

Tags: Production

Comments